The Secret Life of a Simple Man

It’s always easiest to write about a person once you’ve met them. Proper interviews are embellished with personal quirks, ambiance, and body language. Without these things, getting a firm grasp on ones personality becomes a bit of a challenge. Writing about a person before you’ve met them seems like a horribly unfair way to write about a person, anyhow. But considering Gus’ busy schedule, writing about him before meeting him, or ever meeting him, was the only option.

Through a series of voicemails, emails, and short phone conversation one could easily gather that Gus Xhudo was a good guy. He had a conversational tone and an unexpected excitement to talk about Mercy’s Corporate and Homeland Security program. Questions pertaining to the Bachelor of Science degree were easily and eagerly answered. As for the ones pertaining to his line of work… not so easily, or eagerly, answered.

The warmth of his Jersey accent would make anyone believe that he’d share anything. The fact that he’d agreed to talk about his time on the FBI’s Terrorist Task Force or his two years spent in Nigeria supported that assumption. The details he withheld were not excluded because of impatience or shyness; they were just unlawfully a topic for discussion. Any hope of unearthing any other secrets was just wishful thinking.

In 1999, the U.S. State Department conducted a pilot program in Nigeria, Jamaica, and the Philippines. In Nigeria, Xhudo ran the Anti-Fraud Unit, where cash offers were being made to consumers who got conned into transferring money for “safekeeping.”

“It’s easier than people think, really. Go Google yourself. I bet you’ll be surprised how much of your personal information there is on there,” Xhudo persuades. “And that’s before anyone’s tried to go through your junk mail.”

After living and working in Nigeria, Xhudo came back to America. Moving from place to place had always been part of the job description, which is still a little vague, as are the answers regarding his current job.

“It is easy for me to talk about my time as a former Diplomatic Security Service Special Agent now because that’s all public information,” he lends as an apology. “I’m afraid I am not at liberty to discuss my current job detail.”

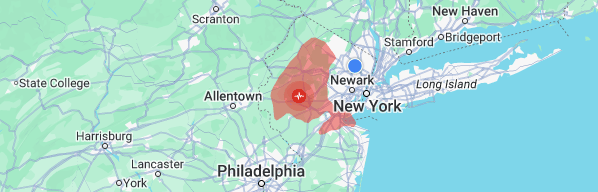

With such confidentiality, it seems kind of obvious that he’s done undercover work. Considering the few voicemails, emails, and short phone calls collected as his only proof of existence, one could say that he’s still undercover. Keeping low profile has always been easy for Xhudo. The Foreign Service of the State Department had the five-year rule about remaining in the U.S. for over that time. Apparently, the best way to keep a man’s face from becoming a familiar one is to move him around a lot.

“Going undercover sometimes takes months to investigate a case. We are creatures of nature. Before we can bang the door down demanding answers we already have to know the answers,” Xhudo pauses. “We have to know who you are, who you live with, your relation to each other, and whether you like cream in your coffee,” he finishes.

His stream of interrogations would make anyone feel uneasy and intimidated. To deny his Jason Borne coolness would be hard to do for anyone, regardless of whether you know what he looks like or not. Truly, to question a federal agent’s coolness would be mistake number one. The second: lie to them.

Xhudo has dealt with foreign fraud, partnered with FBI terrorist joint forces, tackled protection for foreign and domestic dignitaries and has touched down in more than 20 countries. He can smell the sweat beading on the forehead of a scammer and the route you take to work Monday mornings. Yet still, people try to chat their way out of handcuffs.

Half laughing, Xhudo admit to a tactic he claims to be used by every field agent as some point in their career.

“Do you know Martha Stewart?”

He repeats the question, “Do you know who Martha Stewart is?”

There is a bit of confusion as the silence stretches on. Was it rhetorical or was the pause asking for an answer? The moment is filled with a different statement. “Martha Steward was a billionaire, with a B. And guess what happened to her?” Again, confusion tempts the idea of playing along. Not that his questions seemed the type for an eager hand raise.

“Martha Stewart was a billionaire, she had some of the most expensive lawyers and attorneys out there and she went to federal prison. Do you know why she went to federal prison?” His game of questions halts. This last query presents little room for an optimistic ending for the one in question.

“She went to jail because she lied to a federal officer. Now, let’s try that first question again.”

In a game that he knows all the answers to, it’d be stupid for anyone to try and beat him. He doesn’t ask for answers, you’d be wrong again if you thought he was. He’s really asking for your reaction.

“At times it’s hard to stay detached,” he admits. “The job requires you to ignore emotion and focus on reason, which is a challenge when the perpetrator just doesn’t know any better. In the U.S. we are taken care of. People pick up your garbage and we are taught the difference between right and wrong. In places like Nigeria, doing wrong is sometimes the only option for survival,” he exhales.

It’s easy to picture Gus shrugging his shoulders on the other side of the phone as he allows confliction to coat his voice. “They grow up in a word of corruption and learn early that you have to scam.”

Xhudo’s fierce observations are proof that you have to be more guts before becoming a Federal agent. You got to have brains. Before joining the force Xhudo came from an dducation background and has now enjoying being on the other end of an assignment. He’s grading them.

Xhudo has re-embraced his roots as one of Mercy Colleges Corporate and Homeland Security professors. The program offers students a more accurate view into the world of private and public security. Often Criminal Justice and other similar programs, try to focus on those who seek or gravitate toward law enforcement fields. However, Corporate Homeland Security recognizes that the public sector (homeland security) is a vast area that incorporates elements as diverse as drug smuggling investigations to counter-terrorism efforts to natural disaster preparedness and planning.

Who better to teach such a course than a field agent who has spent time in all the corresponding areas? Bringing a balanced approach that offers academic understanding professor Xhudo also cultivates a practical approach. “Unlike most federal law enforcement, my background was not prior military or local law enforcement- it was academic. I respect the need for theory and methodology but am able to infuse this with ‘field’ experience that is still active.”

A typical day for Xhudo starts at 4 a.m. on Monday and ends around 4 p.m. on Friday afternoon. Xhudo assures that sleep happens in between days, but a few hours here and there seem more like glorified naps to the average human. For him, being human is reserved for the weekends. His previous experience makes it easy admire his stamina and uniquely developed mindset. But his modesty exempts a third skill crucial for an aspiring field agent. They have to have guts, brains, and apparently be half vampire.

“It’s definitely a challenge sometimes, balancing work with home life and my family. After a while you gain a certain level of adherence. My wife tells me I’m good at compartmentalizing my emotions,” he admits. “If I’m in a bad moment or if I’ve seen something kind of harsh that day, I have to take a second when I come home to decompress.”

At home, a hot shower and glass of wine usually pull him out of uniform and away from his day. But “decompressing” from a week in the life of Gus Xhudo seems like it would take more than a glass.

The last bit of his interview concludes on a Friday. Every other call had been cut off by the end of his lunch break or confidential calls of duty. His week is finally over and the affirmation in his voice has dropped noticeably by his exhausted “Hello.” His long drive out of the city is spent morphing back to his human self, the simple man that spends weekends “recharging”. He is off the clock but a lingering list of questions are still off limits.

Like two strangers, we fall in and out of small talk about weekend plans and how he believes other colleges will soon emulate Mercy’s distinctive security program. His next three days looked exceptionally light for someone who had spent the past week locking up lord-knows-who for lord-knows-what, until he interjects.

“Want to know a secret?”

Yes. Finally, he had cracked. Who killed Kennedy? Had he been to the Bermuda Triangle and back? What conspiracy was Xhudo about to leaked? He laughed as if he could hear my excitement through the phone.

“All men are simple,” he tiredly chuckles.

It’d be unfair to let his secret go unappreciated as it definitely unraveled the truth behind an old age conspiracy. Yet, the thirst for a classified slip remained. Even now his human instinct to spill a few dirty details for a thrill was overridden by loyalty and most likely some federal confidentiality law.

The call had run on for an hour and it was obvious Xhudo had already shared everything he was allowed to. Though, still curious of what experiences solidified an agents intellectual mentalities and unearthly understanding, he agreed to answer one final question.

His answer expelled the need for a follow up or any further need to pry. Temporarily snapping back into his agent form Xhudo replied, “Unfortunately, I’m unauthorized to disclaim that type of information.”

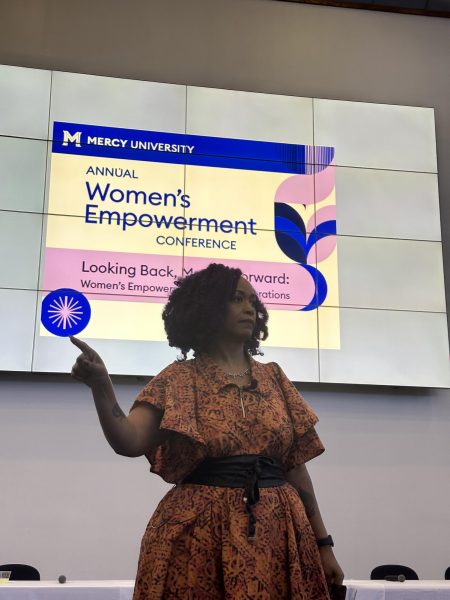

Originally from Florida, Taylor now resides in Manhattan's Lower East Side. She has been fortunate enough to jump between both Mercy's Manhattan campus...