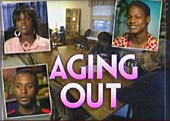

The foster care system that is currently in place in this country has been in existence since the 1850s. It is a system that is criticized by many to be broken, battered and irreparable.

Few understand that the very nature of foster care is short term care, with hopes that preparations can be made for permanent placement. Nearly a half of a million children are in foster care in the United States currently, and less than 25 percent will be adopted and find permanent placement.

The rest are on their own. At the age 21, a foster child “ages out” of the program. And few are able to survive or become successful without a strong foundation of support.

The Casey Family Programs Northwest Foster Care Alumni Study claimed that nearly 80 percent of ex-foster children are doing “poorly” in adulthood.

Roughly 1.8 percent of foster care children go on to earn a bachelor’s degree. The following special report conducted by The Impact features a first person account in part one. Barry Paige, 21, is one of those two percent of foster children that are close to earning a bachelor’s degree. The staff applauds him for his honesty and courage.

The following special report does its best to  condemn a flawed system while at the same time honor those that fight hard for the unfortunate children that are seeking for a place to call a home. It is not a color issue, as roughly white and black foster children stand at 40 percent each. In reality, the issues are poverty, homelessness and post traumatic stress disorder.

condemn a flawed system while at the same time honor those that fight hard for the unfortunate children that are seeking for a place to call a home. It is not a color issue, as roughly white and black foster children stand at 40 percent each. In reality, the issues are poverty, homelessness and post traumatic stress disorder.

It takes resolve, valor and self-reliance, not to mention luck, for foster care children to succeed. The Impact salutes you. As for the system itself, half of all foster children are homeless by the age 18, and 30 percent of all homeless were former foster children. Almost 50 percent of foster children do not finish high school, and a quarter will attempt suicide.

The Impact is hoping society can do better for these children.

Part 1: Barry’s Story Of Fear

I was discharged from Little Flowers Children and Family Services, as protocol, on May 2, 2012.

My 21stbirthday.

At that time, I was finishing my third year at Mercy College. My residency issues for when I finish school were discussed on my last court date, and my social worker ensured me that, as someone in foster care, I would receive first priority in housing. Since I was productive in school, I was also promised a three-month extension on my case to ensure an easy transition into adulthood. None of this happened, and when I finished my junior year of college, I was left financially distressed.

And homeless.

I made various attempts before my discharge, and afterwards as well, to contact case workers, social workers, facilitators and my law guardian, yet to no avail. As a system whose belief it is to foster children until they age out, this agency has not fulfilled its purpose. Justice begs to be served!

This was the short explanation emailed to the director of foster care at Little Flowers Children and Family Services in Brooklyn. In hopes of receiving coverage, it was also forwarded to news channels and various major newspapers, including the New York Times and the New York Post, but there was no reply from any of the newspapers or channels. The director responded by phone, citing misinformed case planning reports.

Over and over again I heard the words the same words.

“You are 21 and there is nothing we can do for you,” blared from the receiver. That phrase smacked into the face of a frustrated adolescent who was down on his last hope. With all hope abated, the phone conversation ended and no further inquiries were made.

I am the product of a corrupted foster care system. Since the age of six, homes have seen the slim frame of a young boy come and go. In a world where dreams are strong, faith is bitter, and stability is in shambles, you would think the foster care system would send relief to someone who is blinded by the future. But that’s a fairy tale. The system does little to engage in the care of fostering a child on the other end of physical and mental abuse. They are more concerned with telling me what I should and need to do, than actually doing something for me. After a while, I learned to care for the system as much as they cared for me – none. That was okay for them, unless there was a court date with the judge. There would be months where I wouldn’t hear from anyone at my agency until we all had to meet with the judge. Then, they would rush me in, and ask hurried questions.

Since entering foster care, my life has been an emotional roller coaster. My foster mother, whom I lived with the longest in my life, passed away in 2005. My aunt, who was my foster parent before I went to college, passed away early this year, a month before my 21stbirthday – the year when I would age out of care. Both were essential people in my life whom I revered and respected as individuals. With the knowledge and love they passed onto me, I moved forward.

My freshman year of college, I was brought to school by my then current social worker (workers were switched a lot), who was very adamant in ensuring my financial safety. Knowing my room and board and books were paid for, and my tuition handled by financial aid, grants, and loans, I eagerly prepared for a year of social and academic success. This went well. But sophomore year, there was a mishap and I was kicked out of the dorms due to misconduct. Was it harsh? Possibly, but I broke a rule, and I was forced to deal with the consequences.

I was 19, homeless and hungry. But I still had to attend classes. By putting my possessions into storage and receiving minor help from my girlfriend and friends, I was able to maintain a rough living situation and travel to campus to attend class during the week.

In the meantime, I was writing appeal letters and apology. I explained to them that I was in foster care and it was a process in moving an adult into a home. I was told, “There’s nothing we can do.” ‘

I remember praying to God.

I never thought I’d have to say this but all I want for my birthday is a home.

My prayer was answered weeks later when my social worker told me they found a home for me in Long Island. Arguing that it would be too far of a commute for me to resume my education, I was placed at a home in Brooklyn. For the remainder of the semester and that summer, I dealt with an unfamiliar setting, a long distance commute, readjusting to new house rules and having to get along with my new foster brother and sisters. Nevertheless, I gained new relationships and a further understanding of independence as I continued to age. I listened intently to my foster mother as she explained what I’d endure after my 21st birthday when I aged out of care, if I didn’t stay focused.

My junior year, I returned to the hallowed halls of residential life. It felt good to be back but I was also aware that it was my last year in care and that I would need to find a place to live by summer, or face being homeless again. During the year, I searched for a job but the economy was poor and employment was at a low. I wanted a place to stay long before I was faced with having to part ways with friends waving goodbye to a homeless adult. Searching for homes was very difficult, but my worker assured me that because I was in foster care, I was first priority in receiving housing. I was also promised an extension on my case after my twenty first birthday because I was doing so well in school. With this information, I felt at ease and stopped worrying so much about where I would reside because I knew the agency would safely transition me into where I needed to be. I was highly mistaken. By the time May came around, I was left with unanswered phone calls, no responses to voice messages, and uninformed workers who told me my extension was up in the air. I hastily called a friend who was in care but had her own place, who let me stay with her until I was able to go elsewhere. The final answer I received from everyone was to apply for public assistance. Sadly, I applied, but it was much more a hassle than an advantage.

A senior at Mercy College who majors in social work is also in foster care. She has dealt with similar problems.

“The system has benefited me financially. They help pay for my room and board, as well as tuition through programs like bulletin 17 and ETV (Education Training Voucher). They could have done better to benefit me by accommodating my school vacations and summer.”

Her frustration at her own housing situation was apparent.

“How can the system foster anyone if they are absent at pivotal moments? It is an inconvenience to try and stay with someone during vacations, when they may have their own plans. How do they know of my safety during these times when they don’t contact me and figure out a plan for where I am going to go?”

Mutual frustrations were agreed upon and responses such as, “I know exactly what you mean,” escaped from my mouth. It was definite that I wasn’t the only student who dealt with these issues, and students from other colleges were most likely dealing with the same dilemmas.

“The experience has helped me transition into adulthood because I have gained independence,” my friend continued. “I am doing laundry, getting meals and buying toiletries on my own now. These are minor survival skills that adolescents need.”

When asked if she knew exactly what the foster care system was supposed to be doing for her she flatly responded, “No. Case workers need to be more effective. They encourage us to do well but don’t actually take part in doing so.”

She said that encouragement can come from anyone, such as peers, teachers, and advisors but that, whoever it comes from, it is a necessity.

“It’s a problem,” she adds. “It’s like you’re blowing in the wind.”

And after the age of 21, some foster care students feel the system wipes their hands clean of them.

I wish there was a handbook for college students on what to do after they graduate. It’s as if the system wants you to follow whatever they tell you and in that way, they dictate.”

Given that my friend has overcome such obstacles, she feels equipped to offer advice so others can avoid the same problems.

“For those that are in foster care and entering college, I would let them know to work hard, stay focused and to network with peers and mentors. Also, secure a place to stay during the vacation and summer.”

She also refers to the struggles of aging out.

“Do everything you can while you’re in care because once you turn 21, that’s it. Apply for housing, stay positive in school, and don’t let the workers misinform you. It’s easy to fall into traps, and frustration becomes your best friend because you don’t know what you don’t know.”

While foster care may sound like a system that aids those that are misfortunate, that is far from so. There are more inconsistencies than successes and more unhappy adolescents leaving than miserable children and teenagers entering. Not that all agencies are misconstrued, but the government should keep better watch on the system they employ to govern those in great need.

I am now a senior at Mercy College. I’ve aged out of the foster care system and have adapted to independence in my own way. Even though I was eligible to leave care at the age of eighteen, I decided to stay because I thought it would be beneficial as I continued my college career. Although it has, it’s always been very unclear on what exactly was being paid, how it was being processed and when it was complete. There have been many times where I had to be excused from the director of Financial Aid because the agency was late on payments. I have noticed that when they needed something done on my behalf, the agency would make strong attempts in holding my attention but when the script was flipped, it remained absent.

Over the years, I expected to receive not only some financial help, but encouragement, guidance, communication, assurance, and positive feedback. The system has done little in caring for me while in college and barely anything before that. My transition into adulthood has been a rough and difficult one and I hope other youth in care who are experiencing similar hardships are speaking up and taking action. Disgrace feeds upon the souls of those who facilitate youth in care, and false hope resides in the hearts of disadvantaged children who yearn for an understanding of authority and belief in a corrupted government.

So, is this a system of foster care, or a list of foster fears?

Part 2: Fighting For The Children

It’s move-in day on a college campus in upstate New York. A freshman surveys her new dorm room and chooses one of the narrow, twin-sized beds. She and her companion make up the bed with crisp new sheets and matching comforter, and discuss ways to make the room functional and comfortable for the school year.

A roommate is expected soon. It would be their first time meeting.

Sister Marie tells the freshman she can introduce her as a friend, instead of saying who she really is. It’s up to the freshman to tell her new college friends that she comes from foster care.

Sister Marie Hess is the director of the Preparing Youth for Adulthood (PYA) program at Cardinal McCloskey Community Services, a social service agency in the South Bronx that provides assistance to youth in foster care. The mission of PYA is to prepare foster children from ages 14 and up for the day when they age out, at which time they are, as Barry wrote, solely responsible for steering their lives in the right direction.

To be clear, this isn’t Barry’s story, nor is it intended to condemn anyone for past grievances. The foster care agency he grew up with couldn’t be reached for comment, so comparing their services with those that Sister Marie advocates for wasn’t possible, nor was it the goal. More accurately, this can be described as two sides of the same coin, where youths like Barry have to fight their way through the foster care system, while Sister Marie is fighting at the other end trying to prevent that from happening.

Sister Marie, in her own words, is well past retirement age, but has youthful eyes and a friendly, genuine smile. She enters the reception area of the Cardinal McCloskey agency, looking dignified in a deep purple-colored business suit, and a head of silver white, curly hair. She is generous with her time and information, eager to talk about the strength of the kids in her program. Her cell phone is within an arm’s length throughout the interview, taking occasional, short calls to let people know where she is if anyone needs her.

Preparing Youth for Adulthood is Sister Marie’s progeny. When she came to Cardinal McCloskey 41 years ago, their main development programs served children up to age of 12. Sister Marie saw the need to help older foster kids as well, and at the request of the New York City Administration for Children’s Services, she wrote one of the first PYA grants back in 1989, and has been building it since then to ensure the safety and education of every foster child who comes through the agency.

The PYA program is open to foster children ages 14 and up, and beginning at 16, they receive a small stipend for being members. In order to draw people in, Sister Marie hosts occasional Saturday “power breakfasts,” in which she invites alumni to have breakfast with current foster kids and tell them the advantages of PYA. Foster children enrolled in PYA learn about different careers, colleges, and vocational schools, in a mission to empower them, and enable them to be independent self-advocates.

“Our main goal is, we try to bring out the best in them. We tell them their lives have to be in focus if they want to be successful,” said Sister Marie.

Before she came to Cardinal McCloskey in 1971, she was a public school teacher, and that earnest educator’s perspective punctuates everything, Sister Marie says.

“Education is the absolute highlight of PYA. We tell our kids, if they don’t have it, they’re not going anywhere.” That education takes the form of, at the very least, a high school diploma, but the agency also takes them to visit colleges and makes them aware of what the options are.

But Sister Marie is not a strict teacher. She enjoys working with teenagers because she knows deep down they have what it takes to survive, but that there are also times to have fun.

“If we can’t laugh together and play together, we can’t learn.”

She describes how, when she is out and about in the South Bronx, which is where the agency is located, and also where she was born and raised and still lives, she’ll often be suddenly and affectionately surrounded by her kids on the street when they see her.

“Strangers on the street who don’t know us will express concern that a group of teenagers are surrounding a lady my age. I have to tell them not to worry about it.”

Once one of these kids gets into college, Sister Marie is their strongest advocate. Every summer, she and her PYA team will take a handful of students to the Palisades Mall in Rockland County. They’ll invade Bed, Bath and Beyond for everything an incoming freshman needs, which these days, is a lot more than it should be.

“It used to be that we only had to take care of bedding needs, school supplies, and snacks. But now it’s coffee makers and blenders so they can have their smoothies. And of course, cell phones.”

After the shopping trip, the students get taken to their new college, usually located within New York State, since that’s who they’ll receive maximum funding from. She helps set up dorm rooms, and, after making sure they have everything they need, she leaves the student to begin their own new chapter.

To be clear, this is not the story of the idyllic life of a foster child. Youths from foster care who make it into college are in such a small minority, and do so against nearly impossible odds, overcoming hardships that many people can’t begin to imagine. The respect and support that Sister Marie offers is what every child deserves, but not every foster child receives.

According to Pew Research Center, only 58 percent of youths in foster care complete high school, compared to 87 percent in the general population. A slim 3 percent earn college degrees, compared with 28 percent of non-foster care youths.

There are almost 14,000 children in foster care in New York City alone, which creates a large number of potential at-risk youths, and perhaps the most crucial point for many of these youths is their entrance into adulthood. Unlike non-foster kids, whose understanding of how to navigate life is often absorbed while being raised in a stable household, foster youths may suffer gaps in their basic life skills. Making sure kids are supported at least until they can support themselves is crucial.

“Kids from the age of 18-21 who are in school receive no family support. They don’t have families to fall back on, and this impacts everything in their lives, including housing,” said Amy Chou, Program Manager of New Yorkers for Children, a non-profit agency that focuses on helping young people in foster care get educated.

Chou pointed out that they strongly emphasize post-secondary education.

“Whether it’s a two or four year college, or a vocational program, we try to let them know what their options are.”

Once enrolled in college, New Yorkers for Children offers scholarships in which students can receive support for their entire college career, including financial scholarships, mentoring, tutoring, academic advisement, and how to maneuver college life.

Part of that support includes supplying each student in college with a new computer and printer as soon as they enter their second semester of college, as well as a gift card to pay for expensive textbooks.

As for the unique challenges that foster children face in college, Sister Marie points out the impact that a lack of stable family structure can have on kids.

“They might feel insecure and think no one likes them. Sometimes they don’t get along with their roommates.” But she is quick to credit them on their strength and resilience.

“These kids are from hard knocks origins. They usually want to work through their problems on their own. They don’t fold up easily.”

Because they usually don’t receive parental support throughout college, Sister Marie does what she can to fill that void. She keeps a record of what each student likes, and includes those items in occasional care packages, but she also emphasizes that PYA encourages them to be independent, self-reliant adults, a balance that any young person needs.

If, for example, a student runs into problems with their financial aid, Sister Marie will immediately go to the college to straighten it out.

“They have to keep up on their own financial aid paperwork, which can be easy to screw up and cause problems with the Bursar’s Office.”

As to the balance of support versus independence, Sister Marie says, “We don’t enable them, but we also don’t wait for the problem to get worse.”

It seems to be the lack of this integrated support that tore the seams of Barry’s college experience. Sister Marie stressed that kids from her agency who age out receive an automatic extension in care if they are succeeding in college, and she expressed surprise and sympathy that Barry, at one point, was actually homeless.

And while no foster child can be called “lucky” to have grown up in the system, a person’s chance at success can only increase by having a person like Sister Marie in his or her corner.

Within minutes of meeting her, it’s clear that Sister Marie was born to do this job, but she defers any praise and insists again and again that the success lies with the kids, which she made clear in her parting words.

“The kids are the most important. If it wasn’t for them and their willingness to succeed, our program wouldn’t be successful.”

The same can be said about Barry and others like him. If it wasn’t for him, and for his willingness to fight for his success, he wouldn’t be about to graduate and head into the world, a testament to his strength and perseverance.