What if the beliefs that shape your entire life weren’t a choice, but the only reality you ever knew? For David Jackson, Scientology wasn’t just a religion. It was the air he breathed, the rules he lived by, and the lens through which he saw the world.

Born and raised inside the Church in Edinburgh, Scotland, he experienced firsthand how Scientology controls every detail from childhood, shaping identity before one even realizes he or she has one. He never attended regular school. His formal education ended at 11, replaced by courses and drills run by the Church.

“My mum was doing a course and she just brought me along,” he recalled. “They had a kids’ course room, but I was put in with the adults… I remember they were doing TRs, and I just copied what they were doing. Nobody told me I was too young.”

From as early as five years old, Jackson found himself swept into Scientology’s demanding rituals not with other kids his age, but alongside adults.

These “TRs,” or training routines, weren’t mere exercises. They were designed to strip away natural emotional responses.

“You do these drills where someone just sits in front of you and tries to get you to react. And if you do, they say, ‘That’s a button, what’s the incident connected to that?’ They teach you to shut down emotions.”

The constant scrutiny extended even to the smallest involuntary actions. “You’re constantly being told there’s something wrong with you that needs fixing. Even your body language is suspect.”

Scientology, founded by L. Ron Hubbard in the 1950s, is a belief system that blends self-help, spirituality, and a strict hierarchical organization. Its teachings include auditing, training routines and the pursuit of spiritual enlightenment under the supervision of the church. Members are often expected to follow rigid rules, adhere to church doctrine without question, and dedicate large portions of their lives to its programs.

The Church of Scientology does not publish official membership numbers. Its website claims “more than 11,000 churches, missions, and groups in 184 nations” and says it welcomes 4.4 million new people each year. In contrast, The Washington Post estimated between 25,000 and 55,000 active members worldwide as of 2012.

Scientologists remain very secretive about their membership, but keep the numbers of those who leave even tighter. Recently, Mike Rinder, a former Scientology spokesman, made calculations based on the numbers of “Super Power” graduates published in Scientology mailers, came up with an estimate of only 20,000 active current church members.

Paul Burkhart, a former Scientologist, who had worked at the Hollywood Guaranty Building and had access to sensitive church documents, “estimates that four or five thousand Scientologists are on staff, with about 2,500 of that in the Sea Org. Including non-staff “publics,” he would estimate Scientology’s worldwide total active membership between 10 and 20 thousand.”

As part of the Church’s system, moments of public recognition helped reinforce a sense of belonging and obedience. Jackson described weekly gatherings where members celebrated each other’s progress.

“You’d say what you got out of the course, and thank L. Ron Hubbard. Always thank L. Ron Hubbard.”

While these ceremonies gave members a sense of pride and power, he acknowledged the darker side. “It was a ritualized environment to say… like, pat everybody on the shoulder and say how good we’re doing. So, it’s very manipulative.”

However, the unshakable faith he had been raised with began to crack when he came across an obscure and chilling instruction buried in a Scientology text about how to deal with thetans, which, according to Scientology, are spirits or entities which has lived through countless past lives and exist inside human beings.

“It said that you could exteriorize a thetan by shooting them in the head with a Colt .45,” Jackson said. “And I was like… what? You’re told Hubbard is this amazing man, and then you read something like that.”

At just 12 years old, Jackson was sent to the Sea Org, the Church’s inner circle, where members work grueling hours under strict conditions.

“I was in uniform, in berthing, working full-time. Sixteen-hour days, seven days a week, no holidays, no proper food. You’re a kid, but you’re treated like an adult.”

Discipline was enforced through constant surveillance and reporting.

“There’s a thing called ‘knowledge reports,’ and if you say the wrong thing, someone writes it down and sends it to the Ethics department. You’re always being watched.”

Jackson’s experience also revealed the Church’s approach to abuse allegations.

“There was a girl who’d been molested before she joined the Sea Org. She told someone about it, and they said, ‘Well, what did you do to pull that in?’ That was the response. No support, just blame,” he claims. He added that the mindset taught within Scientology made victims feel responsible for their suffering.

“You’re told you’re responsible for everything. That you caused all the bad things in your life, that doesn’t leave you easily.”

As he moved into adulthood, Jackson began to reflect more deeply on his life in Scientology, with unsettling experiences continuing to build in his mind.

“If you can imagine, from my late 20s to late 30s, I was on the fringe, sitting on the fence, just getting on with my life. I wasn’t too involved, but I never spoke out or admitted any disagreements to my family.”

Jackson stayed quiet and played along until, ultimately, it became increasingly clear in his mind that this was something he needed to pull away from.

The urge to break free eventually outweighed the hold that the Church had on him.

“I just got an instinct to take a stand on it, and I just did.”

But breaking away from this life comes with a price.

“I basically announced to my family about 10 years ago that I was leaving.”

At that moment, the disconnection began.

Everyone in Jackson’s life cut him off.

“I’m one of seven. So you can imagine, my brothers and sisters were all kind of quite a little squad together as we grew up.”

The other six now will have nothing to do with Jackson.

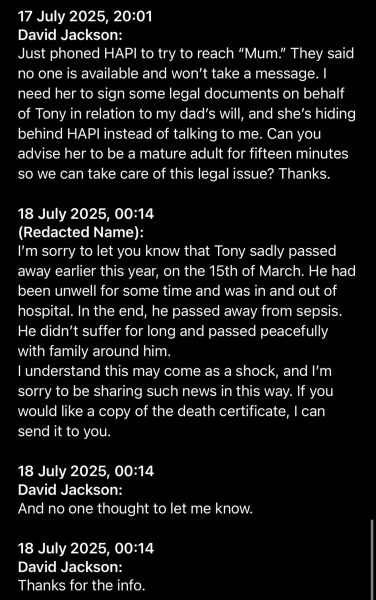

Just two months ago, in July, Jackson found out his older brother, Tony, with special needs, passed away in March.

“Due to Scientology disconnection policy, I wasn’t given a chance to say goodbye. I wasn’t informed of where he was put to rest. I’m on the side of, when it comes to death, you leave politics and religion aside, but Scientology disconnection policy obviously transcends that.”

Three years ago, his father also passed away, and again, he wasn’t invited to the funeral.

Generally, when family members grow up, naturally, people start to grow apart as they reach different points in their lives.

This isn’t the typical case when it comes to Scientology.

“You’re all so interconnected, and what you’re doing with the cult. There isn’t that room with a chance to grow apart. You’re more kind of forever than would normally be the case.”

This level of disconnection is deemed to be the consequence of someone taking themselves out of Scientology and has a lifelong effect on those who leave, he claims.

“I kind of, you know, you can imagine there is a gaping hole in my heart and soul. It’s like losing all of your family in a house fire without there being a house fire.”

Yet he adds that with such hardship comes clarity.

“I would like to say that personally, out of all the experiences, I’ve walked away from it all with very much a sense of I’m a spiritual being, and I’m a spirit.”

With the help of therapy, Jackson found an outlet in blogging. On his blog, Dortju, he discusses both his critiques of Scientology and his respect for scientific advancements.

“The blog was just a chance for me to say what I wanted to say. I wanted to say as much about anticult movements as I did about cult movements and have a dig at how cultish the military is as well, because I just disagree with that.”

Aside from a blog, Jackson has also written three books. A fantasy book, a book on events in World War II through a fictionalized character, and a third book titled “The Devil’s Lieutenant’s” about Aleister Crowley, L. Ron Hubbard, Jack Parsons, Charles Manson, and their connections to Scientology, Black Magic Church, and science.

At Jackson’s point in life now, he can offer words of encouragement to those currently associated with the church who may be in the same position he once was.

“If you’ve found a comfy spot on the fringes where you can stay friends with family that’s dedicated and not have to be involved, stick to it. Don’t leave like I did. Just sit on your little sweet spot, stay on the fence, and be happy.”