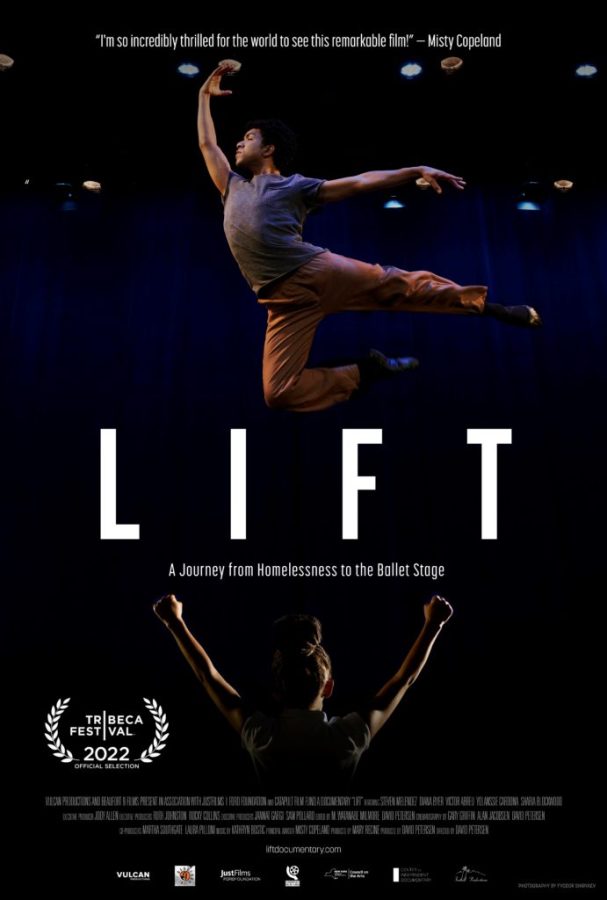

LIFT: A Ballet Story

Mercy Alum Tiffany Cordero sees her blood, sweat and tears of ballet come to life in award-winning documentary

If her eyes are to be believed, Tiffany Cordero was about to see her life’s work shown across the Tribeca Film Festival for thousands of people.

This rapid, heart-pumping minute can be traced back to a quiet but bustling moment in the city when little Tiffany was indifferent towards her mother suggesting she start taking ballet.

Her mother had caught wind of the New York City LIFT Program, or Project LIFT, a chance for homeless and at-risk students to participate on the stage, courtesy of the New York Theatre Ballet.

When Cordero first joined this program, she was in the shelter system with her family. Now, as a Mercy College graduate with a degree in business, she gets to reflect on her past with her friends and family who helped her on the way.

The documentary, directed by Oscar-nominated David Petersen is a multiyear-long production about the hard dedication and passion that goes into ballet. Ballet was her one constant. It was what kept her grounded in a lifestyle that required continuous moving and consistent adjustment.

And it’s fortunate that this program is around.

Brought to life by Diana Byer, Project LIFT was started in 1989 with the hopes that this activity could bring illumination to the lives of children from homeless shelters.

As stated on the program’s website, “When the children are very young, they want to succeed in life. As they get older, they begin to see that they have little opportunity.”

Cordero identifies with these feelings.

Oftentimes, talented children are rejected from programs like this because they don’t have the funds or resources needed to be accepted. People of color, and those from lower-class families don’t even get the chance to prove themselves.

“Unless you’re at the dance studio of Harlem or Alvin Ailey, you’re not really going to see a classical ballet class full of people of color which is unfortunate because those two places shouldn’t be the only safe places for dancers of color.”

A quick Google search would share that New York City has tuition prices starting from roughly $2,000 for just a quarter alone. These programs are for parents who don’t have to decide between school or allowing their child to be cultivated in the arts.

“It’s incredibly expensive. It’s almost as if its gate kept shut,” Cordero said. “Marginalized communities don’t often have that opportunity.”

The LIFT program is a significant crack in this system.

It offers multiple classes a week to roughly 30 children who can study for a 39-week course on scholarship, with an additional month in summer available.

Though the number of children they serve is relatively small, the difference it makes in their lives is astronomical.

These children who are always moving get to have a place that feels like home. The work can get tough. The training is hard, the conditioning is worse. But ballet teaches discipline.

“I do ballet. This is me,” said Cordero. “It gave me an identity.”

Cordero was a very talented ballet student. She ate, slept, and breathed ballet. Because of this, she was able to go on tour with the New York Ballet Theatre when she was barely 13 years old. She traveled the world, living on a bus for weeks on end. The experience was rare and life-changing.

A New York Times Article “Small Steps, Big Dreams” in 2009, Cordero was featured for winning a Van Lier Fellowship, which provides support for gifted children who are seriously dedicated to a career in the arts.

“I want to do the whole Broadway thing — singing, acting and dancing,” said Cordero, who was a 14-year-old sophomore at the High School for Arts, Imagination and Inquiry in Manhattan. “For students of all ages, ballet builds character and discipline, qualities you can always take with you out in the real world.”

Yet this doesn’t come for free. The students sacrifice a lot to succeed at this high level. There’s no time for sleepovers or birthday parties. They barely socialize outside of the dance studio.

But, as Cordero said, when 10,000 people are clapping for you every night, it’s worth it.

“There’s tradeoffs to everything and that was mine and it’s something I’m fully okay with having sacrificed.”

For these children, who change schools quite often, it’s not like the alternatives were available. The ballet studio was their best friend. And director Petersen recognized this.

Petersen had heard of the LIFT program through word of mouth and arrived one day at the studio out of curiosity.

He never focused on what some might view as the obvious. He never outright said, “How does it feel as a homeless child to have this scholarship?”

He accepted the children beyond their home situation.

“Why do you dance?”

“How does this make you feel?”

These were some of the questions Cordero recalled being asked.

His documentary, LIFT, put a spotlight on each student’s personal story. On the LIFT documentary website, it states, “turning a hidden trauma into dance.”

Though these children are offered a life-altering gift, the opportunity doesn’t change anything. Ballet is a tough endeavor and that doesn’t change just because of a scholarship.

Cordero embraced the art form and all the hardships that came with it.

At one point, she did have to take a break. The pain from her ballet shoes, and the physical toll had finally run its course. Cordero did consider quitting for a moment, but when she found herself longing for the ballet studio, those thoughts went away.

That break only reinforced her love for ballet. She danced well into her sophomore year of college. But unfortunately, there are just some things that must be accepted. There’s a point when the body becomes tired and is begging for its host to recognize that. The labral tear that came for Cordero that year was that point.

Cordero had to learn something. How to love something and know when it’s time to give it up.

She asked herself, “Is there anything more that I can do?” And when the answer to that question came, she knew she had to let it go.

Cordero retired from ballet and focused on business, where she took an interest in marketing and journalism. She earned her bachelor’s in business through Mercy College with a minor in media studies.

There are few moments when the realization that everything you’ve worked towards finally paid off. The Tribeca Film Festival sees thousands of visitors each year. Seeing one’s life’s work on that screen counted as that moment for Cordero.

The documentary went on to win the 2022 award for Best Documentary at the San Francisco Dance Film Festival. Although Cordero is done with her time on the stage, ballet is still with her.

She now teaches ballet classes apart from her job, guiding today’s youth to their dreams and more. Cordero is beyond satisfied with her life but if she had to change something it would’ve been to take more risk.

“If we do anything, it should be to take more risk because the people who genuinely believe that they can do something, end up being the people who actually do something.”

Diannah Plaisir is currently a senior at Mercy College, pursuing a degree in Media/Communications. Having decided that she was going to be a journalist...