Liberty and Justice For Some

The Plight of Modern Immigration

May 9, 2013

The America we have come to know is one that is built on the backs of immigrants; beyond Native Americans, each one of us can trace our lineage back to an immigrant. There was a time when the United States of America welcomed immigration with open arms; however, that time has passed. The post-9/11 Homeland Security Act has led to stringent border patrol, increased deportation of undocumented immigrants and changes in visa policies, making education and tourism more challenging for foreign visitors.

In the meantime, immigration into to the United States continues, sometimes legally and sometimes not. Many people risk their lives attempting to enter as a disturbing number don’t survive the often treacherous journey. Progress is being made on several fronts, though. The Senate Judiciary Committee is currently ironing out a comprehensive immigration reform bill which would place many of America’s 11 million undocumented immigrants on a path to citizenship. And the Associated Press is now recommending that news organizations remove the term “illegal immigrant” from usage, a recommendation that may seem trivial but may, in the long run, take the criminal connotation out of undocumented immigration and replace it with a more humanizing phrase.

Dying To Be an American

In 2012, 172 bodies of Mexican nationals were found in the Sonoran Desert, a treacherous portion of the Southwest that stretches across the United States and Mexican borders. The journey into the United States has become more difficult than it was in the past, and although fewer people are embarking on the journey, more dead bodies are being recovered than ever before. The fence separating the two countries has been expanded, repaired and tightly monitored but almost 700 miles of fence is impossible to protect. The fortification of the border has driven migrants deeper into the harsher areas of the desert. The new routes taken are far more deadly, typically taking migrants from all over the world 3-5 days to make it into the country.

The journey is one that many don’t survive, and some of the bodies recovered are those of women and children. Over 4,000 deaths have been reported in the last decade. The amount of bones found in the desert has gotten so extreme that Arizona had to employ a Forensic Anthropologist to help identify the remains. The Pima County sheriff’s office has been doing 200 more exams per year than they had done previously, according to Dr. Bruce Anderson, and have had to create a position which was filled by Dr. Angela Soler.

“This isn’t just a few individuals who die crossing the border. This is hundreds of individuals,” she said.

Currently the Tucson, Arizona morgue has over 800 unidentified remains. When immigrants are found, they are usually carrying some treasure that they have decided to bring with them on the journey; they bring pictures and charms, and usually hide some form of identification on them. Robin Reineke, a cultural anthropologist who also works identifying bodies, describes that the harsh conditions of the desert can decompose humans remains quickly, making identification of the remains difficult.

“Immigrants are being blamed for a lot at the moment- they’re being scapegoated. I feel that these people were by and large, good, hard-working people that did not mean any harm. By attempting the crossing they were trying to do the very best for their families.”

Reinke’s work helps families get closure and gives migrants back their identities. Many of the families contacting the medical examiner’s office are from Guatemala.

“Undocumented people have been dealt a raw deal. The way they are treated is unjust and unwarranted, and I’m in favor of extending citizenship to hard workers,” said Reineke.

Bodies found in 2013

The Journey

The journey into America is nothing like what most American’s assume, and is far different from the time of arrival to the welcome of Lady Liberty. Crossing the border is a trip that takes a lot of preparation. First, one may enlist the help of a human smuggler. Those who smuggle people across the border are the real criminals that Border Patrol actually look forward to arresting, they say. The smugglers, also known as “coyotes,” charge people in excess of $2,500 to smuggle them across the border. The Mexican government has taken steps to warn their citizens against employing the services of coyotes by printing a pamphlet that gives tips to those who decide to cross.

“They can deceive you by assuring you they’ll cross you [smuggle you across the border] at certain times over mountains or through deserts. This is not true! They can put your life in danger leading you through rivers, irrigation canals, desert areas, along railroad tracks or freeways. This has caused the death of hundreds of people.” –Guia Del Migranto Mexico

The trek across the border is not just a long hiking trip. The coyotes that organize the walks are strict and take routes frequently used by gun smugglers and drug cartels. After entrance into the United States, immigrants remain under the control of coyotes until their debt has been paid. Coyotes keep tabs on the people they bring across the border to ensure that they will not contact the authorities or try to turn them in, usually using threats and extortion to keep their shady businesses secret.

Frequently, immigrants are minors who cross the border looking to meet up with relatives who have already made the journey, or heads of families looking to give their loved ones a better life. Drug cartels and coyotes are not the only dangers faced by migrants; the terrain alone is a death trap to many. Bringing water is vital to survival, unfortunately many making the journey end up drinking tainted Mexican water which leaves them violently ill.

Temperatures in the Sonoran can reach as high as 134°F in shaded areas and drop to as low as 32°F at night. The desert heat frequently melts the shoes of migrants, sometimes causing burns and other damage to their feet. When bodies are found, they are normally identified by their unique clothing. Before making the journey, people construct special garments to protect themselves from being robbed by unscrupulous coyotes or the cartel. Breaks are limited and migrants are forced to walk for hours at a time with seldom 15 minute breaks. Migrants are often told by coyotes that the walk will only be one or two days when in reality, it can take up to one week to cross the harsh desert. If any member of the group becomes ill, coyotes will leave that member to die in the desert. They often assure the others that they will return for them, but the reality is that they come back and steal water, identification and cellphones from the victims, expediting their deaths so they cannot confess anything to authorities.

“Don’t let him out of your sight; remember that he’s the only one that knows the terrain and therefore is the only one that can guide you safely.” -Another coyote warning from Guia Del Migranto Mexico

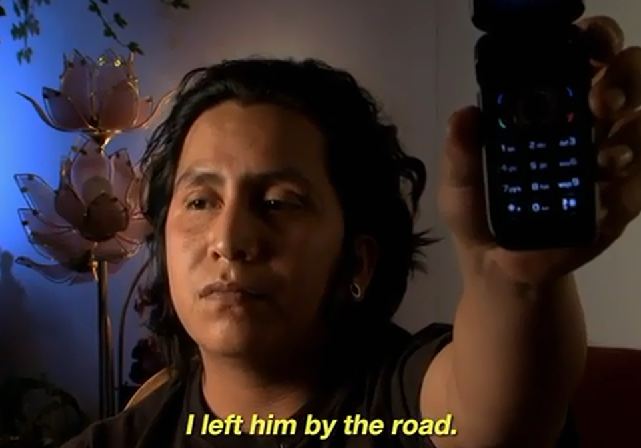

“The Undocumented” is a documentary which follows a man who crossed the Sonoran looking for his father, Fransico Hernandez, who had previously come up missing after making the journey. During a taped phone conversation, the coyote blatantly admitted to leaving the man’s father in the desert, and blames the victim.

“It was his fault because he couldn’t walk anymore. I told him to stay and turn himself in.” Fransico Hernandez has yet to be found, and his family holds on to hope that he somehow escaped the Sonoran.

There are an estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants currently living in the U.S., and one whose status has made some progress recently is Antonio Alarcon, 18, from Queens. Alarcon’s border crossing from Mexico involved crossing the desert and facing a series of physical hardships.

“My family and I walked for three days. It was scary for me, but it was really hard for my parents.”

Alarcon, then 11, recalls the leader of their group telling them to discard all food and water as they approached the U.S. border, but the guide was mistaken and off-track. The border was still more than half a day’s walk away, and now it had to be made without provisions.

Once they entered California, the family boarded a flight to New York City and moved into an apartment already overflowing with relatives. Alarcon’s brother had been left behind with his grandparents, too young to make the difficult trek.

Border Patrol

The number of people trying to cross the Mexican border to enter the United States has dropped significantly; however more bodies are being found than ever before. After apprehension, the migrants are brought to court, charged and either detained or deported. Upon deportation, many migrants try to re-enter the desert, only to realize that the U.S. Border Control now buses people deeper into Mexico so that it will not be easy for them to re-enter. Many Border Control agents do not consider migrants criminals, and usually carry around gallons of water for them. Not only is it their job to protect the border but to save lives of the very people they are trying to keep out.

American Views on Immigration

According to Pew Research Center, the majority of Americans agree that something needs to be done in regards to illegal immigration; however they also agree that a pathway to legal immigration needs to be opened. Most undocumented immigrants are native to the countries that surround the mainland U.S. or have become illegal on an expired visa.

In this economy, every political issue is rooted in concern for the fiscal health of the United States. Conservatives argue against illegal immigration, claiming that the undocumented take jobs away from Americans.

“Our focus should be on ensuring every U.S. citizen who is willing to work has a job instead of (filling) jobs with foreign laborers,” said former Rep. Elton Gallegly, who believes illegal immigration is the reason for high levels of unemployment. Gallegly argues that the under-skilled Americans who need manual labor jobs are being turned away in favor of the undocumented, who work for lower wages.

Others argue that undocumented people are able to receive American benefits without contributing to them in anyway, while also sending money back to their native countries and not spending it in the U.S.

Common misconceptions among people who are unreceptive to the idea of immigration reform believe that undocumented people are receiving American benefits without contributing to society. Although it may be true that illegal immigrants who are being paid “under the table” may escape some taxes, they are still subject to property tax and sales tax, and contribute to benefits they will never be eligible for.

“I was under the impression that the undocumented can receive benefits through their children who were born on U.S. soil,” said Bianca Bailey, a psychology major at Mercy College.

According to federal law:

Notwithstanding any other provision of law and except as provided in subsection (b) of this section, an alien who is not a qualified alien is not eligible for any Federal public benefit. Exceptions to this law are “Medical assistance under title XIX of the Social Security Act for care and services that are necessary for the treatment of an emergency medical condition and are not related to an organ transplant procedure.

Another reason for the ironic stigma against immigration is because Americans fear that people who opt out of legal immigration have something to hide, which is especially unsavory in this post 9/11 world. Public opinion toward immigration is more positive among individuals who have graduated college, while individuals who have not graduated high school tend to have negative opinions about immigration, according to Pew Research Center.

Illegal Immigration Impact on Jobs

Many of the jobs that the undocumented end up having are jobs that many Americans simply would not do, due to advancement of education in America. American’s are fully aware of their rights to a fair wage, and more Americans are overqualified for the type of

low paying manual labor jobs usually given to the undocumented. Many undocumented workers work in agriculture, and do valuable jobs that aid in many aspects of our daily life.

The stereotype that undocumented immigrants work as nanny’s and taxi cab drivers are unfounded.

Fifty-eight percent of taxi cab drivers are native born, or are legal immigrants because of the documents needed to operate a cab, such as a license and many different permits.

Sixty-five percent of ground maintenance workers and construction workers are native born, and 75 percent of janitors are native-born.

Getting a job in the U.S. without paperwork is exceedingly difficult. Jobs procured by undocumented immigrants pay under minimal wage and offer no benefits, employment rights, or job security. According to Jim Gilchrist, president of the Minuteman Project, a group dedicated to anti-illegal-immigration, “As long as the laws are not enforced, cheap wages with no benefits will continue…. You take that out, the low wage element out, and you’ll see American citizens applying for jobs like landscaping, shoveling concrete, because wage rates will go up, and they’ll come with retirement benefits and unions.”

Companies exploit undocumented workers by paying them low wages and offering them no benefits, many argue that if we allowed undocumented workers to report this exploitation without fear of deportation it would open the job market for American workers and undocumented ones.

Eighty percent of Americans agree that companies that hire illegal immigrants need to be shut down.

Tales of Immigration

Roy Naim doesn’t quite fit the frame that undocumented immigrants are often painted into. His illegal border crossing occurred somewhere over the Atlantic Ocean, and didn’t involve human traffickers or days of hiking in extreme desert conditions.

He was born into an Orthodox Jewish family in Israel, and his family came to America on a visitor’s visa when Naim was four years old. The visa expired. The family stayed.

Now 29, Naim is an aspiring marketing consultant and has been a volunteer in his Brooklyn community for much of his life. He has visited patients in hospitals and delivered food to people in need. Once, an organization rejected his offer to volunteer because he didn’t have a social security number. He was devastated, but not totally unacquainted with the feeling.

“The journey of an undocumented immigrant isn’t an easy one,” said Naim, and added that it often includes uncertainty, depression, and the isolation of being different.

“I used to be embarrassed to admit why I couldn’t get my driver’s license, so I would lie,” he recalled.

Other memories of realizing he was different from his peers include a trip to the hospital with a broken leg, where he was denied treatment due to lack of health insurance. Another time, his eighth-grade class was taking trip to Niagara Falls, on the Canadian side. His parents refused to let him go.

In both of the above cases, Naim’s high school principal stepped in, first paying his medical expenses in full, and later providing Naim with documentation so he could go to Niagara Falls with his class.

“This was my first experience with an underground railroad,” said Naim, speaking of the network of American citizens who assist undocumented immigrants simply because they feel it is the right thing to do. “I understood then what it meant to be undocumented.”

Naim, who has only ever identified as American, in his eyes, is a living argument that immigration reform is long overdue. The proposal that the Senate has recently drafted, and that is currently up for significant amendment, does address the needs of people such as Naim, although the proposal isn’t without controversy.

The reform was drafted in April by a bipartisan Senate committee known as the Gang of Eight. Currently, the 800-plus page document proposes granting provisional legal status to undocumented immigrants who arrived in the U.S. prior to December 31, 2011. That status would then place the immigrants on a 13-year path to citizenship.

In the United Sates, children have the right to receive an elementary and secondary education, regardless of their immigration status. Social security numbers are not required, nor is it lawful to require parents to disclose their residency status. Out of approximately 3 million annual high school graduates in the U.S., approximately 65,000 are undocumented immigrants.

Antonio Alarcon, the young man whose parents brought him to America when he was 11, became consciously aware of his situation around ninth grade. He was not a legal resident of the country he now considered home. Where high school was challenging because of the language and cultural barriers, college was going to be a financial problem. Though many New York State colleges allow students to enroll despite their residency status, there is no financial aid available for undocumented immigrants.

After Obama’s election in 2008, Alarcon began to see how the willingness to fight for one’s beliefs could actually change the course of the future. Flashes of hope began to inspire him, and he became involved in his own cause.

“Obama was fighting for the future of the U.S. so I saw that you can fight and change things,” he said.

He’s been to Albany twice to rally in support of immigration reform. On one of his visits, he stood up in front of state politicians and told them his story. He described how he works hard every day to make his grandfather proud of him, sometimes staying up all night to study for a test. He talks about his academic accomplishments, and how he volunteers in his community by going to hospitals and visiting patients who otherwise wouldn’t have visitors.

Through all this, Alarcon resists defining himself as an activist.

“I just want to help the people in my community who need help, and I want to go to college.”

His dream is to become a journalist.

Just before Alarcon was slated to graduate high school last year, his parents returned to Mexico. The grandparents had died so someone needed to take care of Alarcon’s younger brother, Salvador, whom Alarcon hasn’t seen since leaving Mexico. They were also having an increasingly difficult time finding work in New York.

He is hoping that the immigration reform bill will eventually pass, and that it will allow his parents to return, along with his brother. The bill currently states that in some cases, undocumented immigrants who have been deported will be allowed to return.

“They self-deported,” explains Alarcon, using term made popular during Mitt Romney’s run for president last year. It became too difficult to get by in the U.S., so they chose on their own to go back to Mexico.

In the meantime, they missed his high school graduation, where he became the first member of his family to achieve that honor.

In June 2012, the Obama administration enacted Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, which allows for the temporary suspension of deportation of young people who were brought to the United States as children.

Alarcon has been granted deferred status. Naim has been waiting almost six months for his application to be approved.

In a somewhat ironic twist, since arriving in America 25 years ago, Naim’s two siblings have gained legal U.S. residency through marriage, which then aided his parents to obtain their green cards. Brooklyn-raised Naim, who came to the U.S. as the baby in the family, is the only one that remains undocumented.

In the meantime, he lives his life, explaining some of the loopholes that allow him to be a productive member of society.

“I can work as a contractor, but not a full-time employee. I pay taxes.”

Though he is still waiting for Deferred Action approval, he no longer fears being targeted for deportation.

“It’s now the publicity that protects us. People are realizing the stories of our country, and wondering how we can move forward. It’s a question of what kind of country we want to be known as.”

Sharing those stories has been made possible largely through social media. It was on Facebook that Naim heard of Jose Antonio Vargas, the Pulitzer Prize winning journalist who published an article in TIME magazine about his life as an undocumented immigrant.

“His article gave me so much hope, and made me realize I wasn’t alone.” Naim got much more involved in the immigration reform cause, seeking out others like him. He reached out to Vargas on Facebook, asking how he could help, and Vargas was shocked to hear from an Orthodox Jew, which highlighted the fact that this wasn’t only a Latino or Asian issue.

“What social media does is makes us human,” explains Naim. “Some people think we are criminals, and nothing more than illegal immigrants, but social media makes us approachable.”

A vocal opponent to the current immigration reform proposal is the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank based in Washington D.C. According to their recent report, the bill would end up costing the federal government $9.4 trillion in benefits that

American citizens are routinely eligible for, such as public education for school-age kids, Medicare and Social Security for retirees, and services such as fire and police that need to be expanded as communities expand. The report estimates that the new citizens would only pay close to $3 trillion of that amount.

According to a recent report from Pew Research, the public seems equally divided between favoring the bill and opposing it. Thirty-eight percent don’t know how it will affect our economy.

As for Naim and Alarcon, their lives will continue moving along. Alarcon wants to finish college and have his family back with him. Naim would like to visit Israel like most of his Jewish friends have done. The security of becoming a citizen would be a welcome relief, but both young men seem resourceful enough to make the best of their circumstances.

“Undocumented immigrants are some of the most resourceful people I know,” said Naim. “They can get anything done.”

Americans who have just recently received their citizenship feel as though Americans who were born here take many of their liberties and opportunities for granted.

O. Clarke came into the country from Jamaica when he was 6-years-old.

“My father came to the United States to find work because of the better opportunities, after receiving a work visa he got a job as a Chef on a cruise ship and ended up falling in love with an American woman and getting married,” said Clarke.

Back when Clarke entered the country it was much easier to obtain a visa than it is today. Clarke’s father had become naturalized before Clarke turned 18, therefore he had access to an American education which made the citizenship test much easier for him.

“The process of getting my citizenship was not hard, I pretty much received my citizenship through him, although for others it can be quite a long process.”

Clarke continues to explain that if you enter the country legally the process may be long but ultimately simple.

“As long as you came to the country legally and have been a model citizen the process will probably prove successful,” said Clarke.

Clarke appreciates his American status while also embracing his own culture, but is frustrated with American opinions of immigration.

“Actually, I do not think illegal immigration is a bad thing. Of course, there are some people who come here to do bad things but for the most part, people just want the opportunities that used to be offered to the poor, tired and huddled masses.”

He’d like for his fellow citizens to be thankful for their freedom and fortune.

“I think Americans complain about the country without really appreciating what they have, what they were born into, what many people have died to give them.”

Erminia Errante • Jun 11, 2013 at 8:51 pm

This looks amazing and is a kick-ass story!!!! I am so happy we finally got this through and I’m so proud of you guys. 🙂 Enjoy your summer and can’t wait to see you next semester!! <3