Student Celebrates Freedom for Zimbabwe After Mugabe’s Farewell

There it was on Twitter: pictures and videos coming fast on social media. Chantal Ncube, a senior veterinary tech major, was in disbelief. It could not be, she thought. Maybe the work of a troll, she thought for a minute. Students in the microbiology class where she was a Teaching Assistant were unaware of the magnitude of the moment. Robert Mugabe was no longer the President of Zimbabwe.

Ncube released a breath. “Change, finally, that’s all we’ve been asking for,” she said. It was real, not an exaggeration of events. A couple of hours earlier she had learned that Mugabe, the man who had controlled Zimbabwe as its second President for the last thirty years, had been overthrown.

She could not have imagined the outcome when on Nov. 14 the Zimbabwe Defense Forces (ZDF) had taken control over parts of the capital, Harare, and the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation. The ZDF aired a message that this act was not a coup d’état against Mugabe, but an espousal of corruption.

At the end of several days, this claim proved to be untrue, yet it was a peaceful coup, Chantal points out. The principle of peace is held closely by many in Zimbabwe.

“Freedom, democracy, and the ability to make our own choices,” Ncube described the possibilities that had only been dreams hours ago for Zimbabwe. Now, they had chances of becoming reality. The type of chances that first became available to her a little over three years ago when she arrived in the United States.

Ncube grew up in Bulawayo, the second largest city in Zimbabwe located in the upper southwest region of the country. It is a city of roughly seven-hundred thousand people, she described as still possessing a small town atmosphere. She grew up “before things went bad,” going to park, getting ice cream with her parents and friends, and seeing Santa on Christmas. However, when she was fourteen, Zimbabwe’s economic issues drastically worsened.

In 2008, Zimbabwe faced a deepening economic crisis that had started several years earlier. The hyperinflation in Zimbabwe and subsequent devaluation of its currency caused the printing of $100 billion notes that were worth less than one U.S dollar. The economic situation worsened the already existing issues with access to water and electricity. Residents of Bulawayo could go four days out of the week without water and electricity for only half of the day. The capital city was no better off than the rest of the country.

“In the capital city, their water is brown and it’s been that way for years,” she described.

The lack of economic and job opportunities became scarcer with the worsening economic situation. This was not lost on Ncube, as she thought about her educational future and desire to have a career working with animals. Career opportunities in Zimbabwe are so limited that the role of veterinary technician does not exist in a formal sense.

Ncube once volunteered with a veterinarian whose “vet tech” was his gardener who had learned through observing the veterinarian over the twelve years working for him. “It’s not really the most lucrative or recognized field back home. Americans care about their animals a lot.”

America is where she knew she needed to be.

As Ncube stood outside JFK International Airport, the sight before her was incomprehensible. She was in the United States of America with little she could bring with her from home. “I left a lot of stuff. I had to pack everything I ever owned in my whole life, and I think I was only allowed two bags of like 23 kilos,” she recalls.

That day in Sept. 2014, when Ncube first set foot in the United States, her first time outside of Africa, came with an extended application process to be able to come to the U.S. let alone attend college. In a country where the average monthly wage equates to $253 the costs of applications for college can become daunting. The SATs are a couple hundred to start. Just to apply for financial aid will cost students around $80. Ncube’s discussion of the process caused her voice to become softer.

The only place to supply visas to travel abroad for school is in the capital, which can take over five hours by car, before having to stay overnight due to the interview process. In addition, she had to write essays and applications that come with every application to attend a college. Finally, she had to buy items and furniture to fill her dorm room and join a meal plan.

“What did I really know about America?” Ncube pondered this, when she thought back to growing up and preparing to attend school in the U.S. She thought of burgers, fries, the Fresh Prince of Bel Air, and Grey’s Anatomy. She laughs as she remembers watching a lot of videos on WorldStarHipHop and thinking that was what she would see. “I thought it was going to be a lot of fighting, people fighting in the car doors, like throwing each other, so I didn’t know what to expect really.”

It is the unknown that makes her grateful that she could live with her Aunt Nicole and two young cousins: a place to settle herself in an area of unfamiliarity over 7700 miles from Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. A city and a country, she has not returned to since the day she boarded the flight to the U.S. She last talked with her family in Zimbabwe around the Christmas season, but brought her mother’s Bible with her to the U.S.

It is the unknown that makes her grateful that she could live with her Aunt Nicole and two young cousins: a place to settle herself in an area of unfamiliarity over 7700 miles from Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. A city and a country, she has not returned to since the day she boarded the flight to the U.S. She last talked with her family in Zimbabwe around the Christmas season, but brought her mother’s Bible with her to the U.S.

Over the three years Ncube has studied as a veterinary technology major at Mercy College, she has noticed a transition. She notes her accent has lessened. “I fought it for a good year and a half, then it finally took over.”

Yet, her newfound interest in politics was a surprise development. On Nov. 8, 2016, Ncube experienced an anticipation she had never felt before as she watched the results come in for the 2016 Presidential Election. “Oh my gosh, we really don’t know who it’s going to be,” she recalled that night. The uncertainty of an election outcome is unheard of in Zimbabwe.

Both of the previous Zimbabwean Presidential elections in 2008 and 2013 received moderate to overwhelming assessments that both elections suffered from fraud and irregularities. The 2008 election saw violence that resulted in “Tens of thousands of citizens were displaced in the wake of election-related violence and instability,” according to a report by the U.S State Department. Morgan Tsvangirai, the main leader of opposition party Movement for Democratic Change and Mugabe’s opponent in both elections called the 2013 election as “”The fraudulent and stolen election has launched Zimbabwe into a constitutional, political and economic crisis.” These events have caused a lack of interest in the political process. among, younger generations in Zimbabwe.

“You can be someone in your community and make a difference,” she said to the idea that anyone can serve in elected office from President on down in the U.S. However, she finds it a bit strange that celebrities like Dwayne Johnson and Kanye West can be seriously considered as President. Yet, she marvels “It’s a good thing because it does open up opportunities for people to be involved in politics.”

She views a similar wealth of opportunities when it comes to the veterinary field in the U.S. “I’m almost overwhelmed with the number of things. I can go into research, zoo animals, small animals,” and so on. Options she relishes having as it is difficult in Zimbabwe to change one’s career field if they are no longer interested in the work. A reality compounded by parents who pressure their children to enter career fields that have the best job prospects in an economy with little prospects.

“I saw a lot of my friends going through that,” she recounted. A slight smile donned her face when she talked about the option to go into a different field if she decided veterinary technology no longer interested her.

“To me that is the American Dream that I can actually have a choice. I’m not boxed in.” However, the realities of an international student studying in the U.S come with some limitations. She is able to work on campus as a teacher’s assistant, but unable to intern or work off campus.

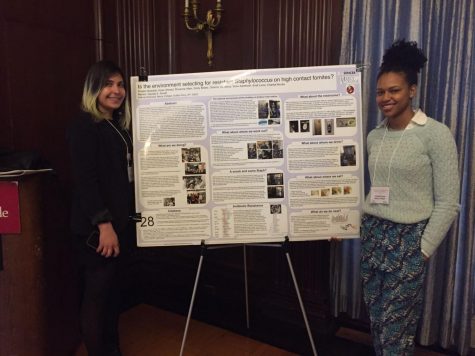

“I just have to try to get as much experience as I can… put myself ahead because I’m competing with Americans who don’t come with this ‘extra stuff’ so I have to find ways to make myself stand out.” Ncube is allowed a year and a half of Optional Practical Training where international students can work in a job of their field, which she plans to utilize upon completing her degree in May.

On the day Mugabe ceded power Ncube realized his removal allowed her and four million plus Zimbabweans who have left Zimbabwe to consider returning in a way not thought of before. “Now, we can actually start thinking about, ‘Yeah, maybe I will actually go back home.’ Now, that’s becoming more of a possibility.”

“It’s a tough one,” she said after releasing a breathe.

Her original plan was to return to Zimbabwe, but she notes that is the hope for many like her.

Zimbabwe’s future remains muddled as it is now lead by Emmerson Mnangagwa, Mugabe’s Vice President until he was deposed by Mugabe, which resulted in the coup that overthrew Mugabe. She believes Mnangagwa deserves a chance and has hopes he’ll open up the country to trade and repair relationships with countries that both broke down under Mugabe.

The uncertainty only grows more with the death yesterday of Tsvangirai. He then held longtime hope, “that [Zimbabweans] could maybe get Mugabe out in a democratic way.” She laments the gap that his death created for the Movement for Democratic Change and opposition as a whole to the ZANU-PF, the political party that has led Zimbabwe since its independence in 1980 under Mugabe, and now Mnangagwa.

In the two months he has been President, she notes not much has changed. Jobs, economic mobility, and basic access to food and electricity appear to remain limited. The electronic transfer of money, once a way to get around the inability to takeout more than $20 a day from a bank, has become the norm. “Vendors on the side of the road use it.”

Her plan for the foreseeable future is to stay in the U.S and work. “I can make a bigger contribution by sending money back home than I can by being home and sitting around cause I can’t find a job.”

The vast unknown and lack of change to be seen in Zimbabwe has pushed her to consider what life would be like for her in the U.S. She never thought working in the veterinary field was an option, let alone, in the U.S. Now, her desire to attend veterinary school does not seem unlikely either. If she is able to attend graduate school, then the interest in dual Zimbabwean-American citizenship is a possibility as well.

The possibilities, options and opportunities are all there.

“It’s just the freedom, the freedom that is crazy and something that is so new to me, but I’m really loving it. Even if I decide I don’t want to be a vet tech anymore, there [are] options for me to branch off.”

Matt Reich is a guy constantly on the go who can't let a minute go unused. Born in a city in Texas, raised in rural Connecticut, and now he's trying to...