World Toilet Day: Changing The Mindset On Our “Fecaphobia”

There are many tentpoles of an advanced civilization. Art, education, infrastructure, technology, transparency, and awareness. An advanced civilization should be one that has eliminated certain “quality of life” needs from being a persistent problem. In reality, our civilization can check many of those boxes off its list as it ascends to higher and higher accomplishments.

Why then is many of our most basic need and aspects of life that every other living being has developed, creatures that we believe to be lesser evolved than we, still an issue?

Why is it that something that should be a basic aspect of all levels of society still needing room for improvement? Why is the issue of toilets even an issue?

This is the goal that the appropriately named “World Toilet Day” seeks to ask.

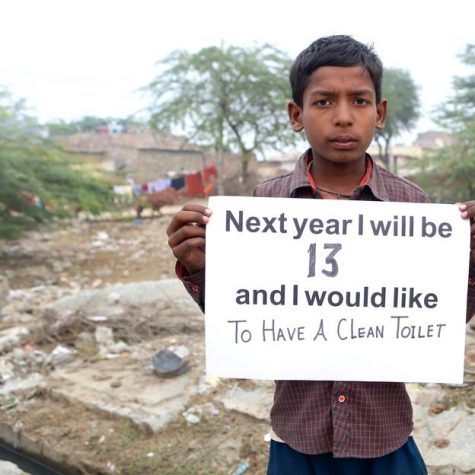

Mercy College recently hosted a discussion that sought to answer this very question. The fact is in 2018, society still has large pockets that lack the availability of something as simple as a toilet, a level of technology that has been around since the age of the Roman Empire.

“There are actually more people in the world who have access to I-phones then access to toilets,” said Dr. Irina Ellison, the chair of Natural Sciences at Mercy College.

The ease of access to toilets and basic plumbing follows the same narrative as many other areas in which certain basic “quality of life” standards are lacking in they are more prevalent in areas of under-development and poverty. Of the over 4.6 billion people who lack immediate and easy access to basic toilet and plumbing needs, the majority of which exist in Africa and India, regions that suffer from extreme areas of poverty and isolated pockets of extreme wealth. Similarly, there is a severe disparity when it relates to a location in the regions as well, the areas that do have a more sophisticated and developed toilet system are bigger urban areas such as cities, while the majority of suburban villages and settlements around are grossly behind.

“There are about 46 countries where less than half of the population have access to improved sanitation facilities,” said Ellison.

A 2015 report from WaterAid, an international charity found that 650 million people lacked access to clean water, and an additional 2.3 billion lacked the same access to safe and reliable toilet systems. The number has since increased. The report also stated that among the three most common causes of death among young children around the globe, one of which is diarrhea, the other two being malaria and pneumonia. The report found that 58 percent of those deaths could have been prevented if those children had access to clean water, sanitation, hygiene.

What exactly consists of a basic toilet system, one that might eliminate some of these issues, and according to Ellison, it isn’t necessarily having a toilet system that American citizens or people in developed areas might associate with, and it involves two aspects. “We are just talking about a very basic toilet, and the concept here is that you are separating human excrement from direct human contact, that those two things will at least initially be separated.”

These systems that don’t constitute a more traditional sanitary system but still eliminate direct contact with humans and their excrement include flush or pour toilets, latrines to a piped sewer system, septic tanks, pit latrines, a ventilated improved pit latrine, a pit latrine with a slab, or even a composting toilet.

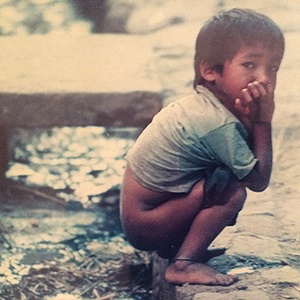

The reality is that a staggering number of people do not have access to such sanitation systems, and that most practice what is called open defecation, “a little under a billion people around the world still practice open defecation, particularly high levels of India, its about 55 percent of the population that practices open defecation which means that they are going out into an open environment with no surrounding toilets,” said Ellison.

And the reality of this issue isn’t limited to specifically sanitation issues, they present another dangerous problem; violence and assault. In Africa, specifically, it is believed that half of the females who attend school eventually drop out because of the risk that comes with the simple task of going to the bathroom. Their reality is that females are at increased risk of sexual assault, rape, and even murder just by finding a secluded spot to relieve themselves as the nearest toilet might be miles away. The risk is even greater at night.

Despite the disparity, and despite the lack of available toilets available, the closest remedy might not be a long process of installing toilets where they are needed, the reality is that with an efficient and dedicated process, the waste can be separated and used in a way that can be beneficial and healthy to the population.

This is the goal of Dr. T.H Culhane, Mercy College visiting scholar and National Geographic explorer. For Culhane, the solutions for such issues don’t have to be limited to areas in desperate need of sanitary efficiency, they can be used in the United States. It all has to rely on us as a population eliminating our fear of waste, or as Culhane coins, our “fecaphobia.”

“There is an urgent need not just to build toilets and clean sanitation systems but to change the mindset of people so they understand what toilets really do, what they are, and what is really causing the problem with them,” Culhane said.

For Culhane, he was once a victim of this idea of “fecaphobia,” it was only a trip to Borneo that led him to realize the missed opportunities and inefficient mindset that we suffer from.

“I know this from first-hand experience having been a fecaphobic American for most of my life who was astonished when I went to Borneo in 1985 thinking I understood biological systems because that’s what I studied, biological anthropology. I get to Borneo in a remote part of the jungle and I have a choice of how I can go to the bathroom, I can use a pit latrine, or I can go in the river and most seemed to be completely insane, where is the flush toilet? And when I say pit latrine it meant walking to a place in the jungle where we have two boards laid down over a pit, a shallow pit, and no barrier at all, it was just the jungle.”

It was this experience that opened Culhane’s eyes for a specific reason, dung beetles.

“Watching with the red glow of the kerosene lantern, the ruby red shining lights of the eyes of dung beetles who immediately sensed as soon as I had started that there was nutrients to be found and came flying with this buzzing like little helicopters through my legs and then flew out carrying the gifts I had bestowed upon them and I was fascinated with this ritual that became part of what my daily life was like for a year. You go out there day or night, you do your business and the dung beetles would be right there and they would buzz in and take it away and after you got over your initial startled feeling of fear you realize these were your little allies and they were making sure those nutrients got evenly distributed so that the jungle could flourish, and you were apart of that as a contributor.”

The experience was only greater exemplified by Culhane’s experience at another village, in which people had commonly used the river as a source to relieve themselves, the effects of which might have been obvious.

Or was it?

“As you move to another site in the jungle, there were no pit latrines, nor did we have the capability to dig them in the time that we were there but there was a river. And I thought, “Ahh” I’ve heard, and been witness to many stories of contamination where people crap in the water and the people downstream get hurt by it,” Culhane said.

Curious by this, Culhane sought confirmation from the local indigenous people of the region, the Maliu tribe.

“I checked with the local Maliu people we were living with and they said ‘That’s only the case if they have overwhelmed the abilities of the fish, here we have not, there are not so many of us’,” Culhane said.

Again, a remarkable occurrence in nature provided an enlightening experience, “I noticed when I went to the river to do my business, the fish came and ate it all up. And then we went at night with lanterns and spears and speared the fish, and the attitude of the Maliu people was your feeding the fish and that’s a good thing. So, I thought this is really weird, now I am learning from two different sites in two different jungles that the fish and the insects and the other wildlife depend on the nutrients that we bring back to them and yet I’ve grown up thinking this is a horrible thing that will cause disease.”

The experience was even more troubling when Culhane traveled to Sumatra, where he had gotten sick from fecal contamination in the water supply, Culhane would seek out the confirmation from the other site he had visited recently. They informed him that the fish had been overwhelmed.

The realization that waste could be used in a productive manner, not the liability that most in the United States had figured, was only the start of Culhane’s journey, one that eventually led him back Mercy College where he and his students would work on another method of utilizing waste effectively, Biodigesters.

Culhane sought to find the perfect blend of human and food waste that would effectively create the perfect environment to harvest the nutrients in the same manner that he had witnessed in Borneo from the Dung Beetles and fish.

Other then Biodigesters, Culhane, along with his wife Enas, and a mixture of students from several universities, created a garden that was fed off the nutrients in toilet waste. The garden, on their fully self-sustaining compound, the Rosebud Continuum, was fed off the waste that filtered out of their home and into a biodigester. The nutrient-laden fluid then would flow out into the garden itself, a Hugelkultur.

Hugelkultur, a German word meaning mound or hill culture, are a form of raised garden beds that utilize maximum surface volume to hold in moisture and raise fertility.

The idea behind it is to ultimately replace septic tank systems, according to Culhane.

“That could be a biodigester, so that replaces the septic tank, and then we get all the gas in the kitchen to cook on. But the overflow of any possible pathogens that weren’t destroyed in the biodigester tank, which does destroy ninety-eight percent of all possible pathogens could then go into an aerobic process that’s living, and create soil every day,” Culhane said.

This process, which Culhane has worked on with not only Mercy College, but also the University of South Florida, where Culhane also teaches is one of the many possible future solutions to help reverse the disparity in the world of a lack of toilets and sanitation systems.

The issue of waste in the world doesn’t necessarily mean the installation of more toilets, rather we can take a problem and create a solution if we only change our mindset.

This is what Dr. Culhane, Dr. Ellison, and many more hopes to change through the existence of World Toilet Day.

Michael Dunnings, otherwise known by the Hungarian equivalent "Miska", is a native of Dobbs Ferry and a senior studying Journalism at Mercy College. Michael...