The Struggle To Survive As A Survivor

Faculty Homicide Survivor Teaches How To Cope With Grief

March 16, 2016

It’s the first day of Managing Human Conflict I. About 20 something students are in a classroom as Dr. Dorothy Balancio stands at the front of the room, preparing to start.

She takes a deep breath, then starts to speak. Her words sound meaningful and filled with sorrow.

“I am a homicide survivor,” Balancio began to say. “My son was murdered.”

The class exhales.

“My lenses are now tinted because of that horrific experience; that’s why I teach this course,” she adds.

“You are now all my Louises.”

Balancio, a Mercy College graduate herself, has taught sociology in the School of Behavioral Science for 44 years.

Before Feb. 4, 1994, Balancio’s life was different. Her concentration in sociology was the role of women in families. She defined herself as a happy wife, a proud mother, good daughter, a loving sister, fun aunt, helpful cousin, friendly neighbor and dedicated teacher.

But in the blink of an eye, everything changed. A life that was full of blue skies and sunshine now had dark clouds and storms.

Her first-born son, Louis, was murdered in a case of mistaken identity. He was stabbed 13 times, destroying his heart, lung, and kidney. His spine was severed with multiple stab and incised wounds.

Balancio, like other homicide survivors, was now condemned to a life of depression and sorrow.

“Losing parents and grandparents, that’s something we expect. That’s the life course,” said Balancio. “But a child, it seemed so unfair.”

When Balancio was married, she did not expect to have a child and bury him. It’s a parent’s worst nightmare, she says.

“It never crossed my mind,” Balancio said. “I was mad at God and everyone around me.”

“It just didn’t fit into my plan,” she added.

And that was why she has dedicated her life to teaching students about understanding grief, coping with it, and if possible, looking to overcome it.

‘I Know What You’re Going Through’

Following Louis’ death, people would tell Balancio “I know what you’re going through” or “the passage of time will make you feel better.”

Others would explain how she should and would feel, but this would completely shut her down.

“I stopped listening to them,” Balancio said, “They knew nothing about what I was feeling, and I wrote them off.”

“Grief has no destination. You don’t just move on with your life. It’s a journey,” said Balancio. “I’d rather someone tell me that they’re there for me, instead of saying they know how I feel.”

People would tell her that as each year goes by, it gets better, but Balancio disagrees with that. Instead, she found that it was harder as the years went by, especially around his birthday.

Louis’ 21st birthday was the last time Balancio saw her son.

“I remember asking him, ‘Do you want me to bake a cake or buy one?’ And he said, ‘no let’s buy a cake so we can spend time together,’” said Balancio.

With that, the Balancio family went out to eat and then back to their house for cake. That’s the last memory she has of Louis as she recalls one of the last conversations with him.

“Sometimes memories are more important than anything else.”

With that in the back of her head, as each birthday came a long, the first one wasn’t as bad. The second birthday without Louis there, it was worse.

“Life kept going on, but he wasn’t there, instead, he was apart of our memories that we live on with.”

***

During the stages of grief, everyone acts differently. There are some people who don’t mind talking about it, while there are others who don’t want to talk at all. There’s no cookie cutter way around grief, as Balancio refers to it. When they’re ready, they’ll talk about it.

This is something Balancio noticed at a corporate party for her husband’s job with people he’d been working with for four to five years.

“None of them knew about Louis,” Balancio said. “He doesn’t talk about him.”

Balancio admits she’s much different. She copes by telling. “You can’t be on a Stop & Shop line with me without knowing about Louis.”

There was a point when Balancio knew she couldn’t share her grief with her husband because she was afraid to.

“I knew how much it was hurting me, and I didn’t want to hurt him more,” Balancio said.

Almost 85 percent of marriages fall apart after a child dies, but Balancio and her husband are in the 15 percent that did not.

“We became interdependent, where we don’t need each other, but we want each other in our lives,” said Balancio. “That’s something I try to teach my students to do with their relationships.”

The grief of losing a child is not only hard on the parents as individuals, but also on others around them. For Balancio, this was her mother, for whom she felt sorry.

“Not only did she lose a grandson, but she lost a daughter,” Balancio began to say. “I was a different person. I was no longer the same daughter she had. I became a daughter of a murdered child.”

Dealing with her mother’s grief at the same time as hers, Balancio knew her mother wanted very badly to help her daughter as much as she possibly could.

That’s when Balancio created what she calls the ‘Happiness Calendar.’

“We would talk everyday and it would be doom and gloom. I couldn’t handle it anymore,” said Balancio.

“That’s when I told her, ‘You have to tell me something happy,’ so everyday she would tell me something that made her smile, and I’d have to find something happy to share with her,” said Balancio. “She’d call me and tell me something that made her smile from that point.”

“When I knew she was happy, I felt the same way.”

‘Family Cheated Of Its Justice’

Balancio became a member of the Parents of Murdered Children organization. There, she’d hear everyone’s stories, and it would bring her back to the very day when she found out about Louis.

She was in Florida at the time; her godmother had just been buried during the day, and that night, she received the phone call from her husband about what to do.

“The first thing he said was, ‘People knocked at the door saying that a body was at Westchester Medical Center and they think it’s Louis. Should I take Jeffrey?’” Balancio started to say. “When he first told me Louis died, he was very good about it. He told me right away, but I lost it.”

“I stood with the phone and just collapsed.”

“I thought he was in a car accident. It registered that he had died and all I kept asking was, ‘Who else was in the car?’” said Balancio. “But my husband kept saying, ‘No, it wasn’t a car accident. It was at a bar. He was stabbed.’”

“‘Should I take Jeffrey?’”

Balancio continued, “From that point on, everything got confusing. Jeffrey was only 14 at the time; I didn’t want my husband to leave him alone, but I kept thinking – why would anyone want to kill Louis?”

Balancio kept thinking it was mistaken identity, that it wasn’t Louis, but if it was, why him?

“Louis’ personality was extremely well-rounded, and he was good at any sport,” Balancio started to say. “When there was any time to pick teams, his first pick would be the kid that no one else would choose.”

“He was always that way.”

With many thoughts in her head, Balancio told her husband to take their younger son with him to identify the body.

“I don’t know whether it was the right answer or thing to do or what.”

To this day, Balancio’s son remembers his older brother lying on the slab with a sheet up to his neck and eyes still open.

With a tear in her eye, Balancio said, “I remember Jeffrey saying to me, ‘Louis looked like he was very much at peace.’”

After hanging up the phone with her husband, Balancio packed her bag and boarded on a plane. By this time, she still hadn’t heard anything until she landed in New York.

“The minute I walked off the plane and saw my husband’s face, I knew it was Louis.”

After finding out the news, Balancio remembers on their way home, they drove by the bar where Louis was murdered.

“All the police tape was gone. It was as if they weren’t investigating something serious,” Balancio said.

The story of that night is somewhat clouded. Exact reasons are uncertain. But the details are that on Feb. 4, 1994, Louis was outside the Strikezone Bar in Yonkers. A member of the Tanglewood Boys, a training ground for the American Mafia, stabbed Louis 13 times, mistaking him for a rival gang member.

Years of odd court room trials and a confession led to a legal loophole, and the suspect walked after seven years in prison in a deal agreeing to time already served.

The Balancio family was aghast and felt cheated of justice.

Fast forward four to five years later after Louis’ death, Balancio noticed the triggers that can set a person off. Living in a condominium, her neighbor was one of the ‘don’t walk on the grass’ people and put up yellow tape to keep kids off.

“I saw the tape and immediately thought of the crime scene,” said Balancio. “I couldn’t even walk into my house. I started hyperventilating.”

The Students Are Her Children Now

During her time of grieving, Balancio said that you find people who will not be able to deal with your grief and admits to losing some friends during the process.

“They thought grief was contagious; they didn’t want to be around me,” said Balancio. “Some close friends who were in my wedding party don’t talk to us as much anymore and when their children were married, we weren’t invited. We would get Christmas cards, that was about it.”

She paused, then added, “I guess they thought if we went to the wedding, we would feel bad because our sons were the same age.”

Balancio is okay with this, though. She finds that the more empathetic people are in dealing with your situation, the more you want to keep them in your life.

“You can’t control the way you grieve,” said Balancio. “Grief is the price we pay for love. The more you love someone, the more you grieve.”

To deal with her grief, Balancio furthered her education with seven postdoctoral certifications, in addition to the Ph.D and three master’s degrees she already had.

“If you look at my resume, it looks really strange, like there’s something wrong,” Balancio said. “But that was my way of grieving.”

By furthering her education, Balancio was able to create a class that would teach her students the necessary skills to navigate through this dangerous world and to open their eyes to the fact that evil exists. This is why Mercy College offers Managing Human Conflict and Mediation courses.

In this course, Balancio teaches her students about trust and about understanding who’s in your friendship networks. She believes that if you don’t trust your intuitive gut feelings, you could have problems, which is what she felt happened to Louis.

“A lot of us are too naive and don’t see through our lenses clearly. We’re trusting people who are hurting us, can hurt us, or will eventually hurt us,” Balancio started to say. “And in some cases, they hurt us really badly.”

“I believe Louis did not know enough to trust his instincts when he perceived evil,” Balancio said. “He was with people who abandoned him, where he died alone, while his ‘so called friends,’ ran away and left him.”

“I’m not teaching this course where we sit in a circle around a bonfire, hold hands and sing kumbaya, I’m teaching a class to make sure all my students understand trust and how to negotiate,” she added.

“I want everyone to be a little more aware.”

Managing human conflict is not just one discipline, it’s considered to be a mutt according to Balancio. When she had the idea in mind, she found legal studies professor, Diana Jeutner, and political science professor, Arthur Lerman, and they would teach the course together.

“We all had different learning styles. Arthur would come in with history books; Diana was the box, she was the ‘this is what we’re doing, no other way,’” said Balancio. “And then I’d come strolling in with a TV set wanting to show movies.”

“We’d fight all the time and students would say, ‘This is conflict!’ And they’d all take notes on us.”

Balancio found that teaching this course was a way for her to deal with her anger and grief. Balancio doesn’t see grief as a sign of weakness or a lack of faith. It just helps us redefine the world because we’re seeing it from a different perspective, which is something she uses while teaching her classes.

She also uses the same techniques that she used when Louis first passed away, such as the Happiness Calendar.

It not only helped her grieve but helps her honor Louis’ life. During the January training, they not only pay a good part of it but feed everyone who participates in it during the six days.

“Mercy does not pay for it,” Balancio said. “It comes from the Louis Balancio Scholarship Foundation.”

Aside from the mediation training, Balancio hopes to expand the foundation to help people who are in the same shoes as she once was.

“I was beat up by the system for more than 18-20 years, and I just want to help homicide survivors when they’re going in court,” Balancio said. “I can help them with their victim impact statements, something I had a tough time with myself.”

“That’s how my grieving process works.”

For Balancio, her students helped her deal with her grief and brought Louis’ life back, each time she taught them. And recently, it’s been through her book for Managing Conflict: An Introspective Journey to Negotiating Skills.

But for other people, it’s different, as she refers to her son Jeffrey.

When Jeffrey got married, he had four bridesmaids, four groomsmen and a maid of honor, no best man,” Balancio started to say. “The maid of honor walked down the aisle with a single rose and a black bow on it, as there was an empty chair for Louis.”

“Louis was the best man.”

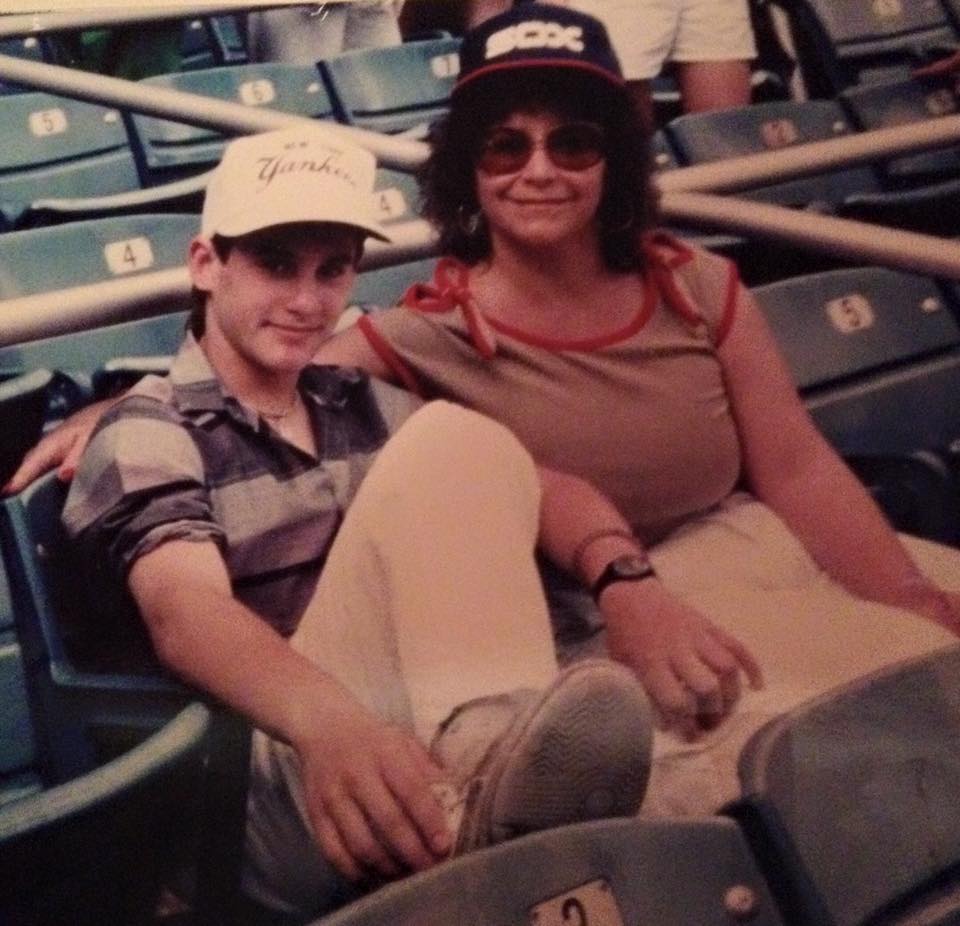

She whips out a picture as she adds, “Fast forward to present day. He now brings his baby to let her know about her Uncle Louis.”

Another person who stands out in Balancio’s mind when it comes to remembering Louis was one of his good friends. He was the same kid that Louis would always choose first on the teams.

“He became a dentist and lives in Washington now, but he makes sure to come home every year for Louis’ birthday,” Balancio said. “He’s the one who puts the beer bottles on the grave.”

***

Balancio doesn’t and cannot forgive Anthony DiSimone, who murdered Louis, for what he’s done, and she knows she cannot live on revenge, as much as she’d like to. The way she puts it is, “Revenge is like holding a burning coal. If you hold it long enough, you burn.”

The only revenge Balancio can give is arming her students and making them more aware. She wants to make them become good negotiators and mediators, not to have people break their trust.

“The way I set this course up was to make everyone more emotionally intelligent,” Balancio started to say. “Become more aware of yourself and more able to regulate your emotions and to be able to motivate yourself.”

“You can live life unfair, but you have to be smart about it.”

It’s no secret Balancio’s students filled the void that she had after Louis passed away. Each and every one of them has helped her through her grieving.

“I don’t have Louis to worry about, to be concerned about, and to guide anymore,” Balancio says.

“My students are my Louises.”