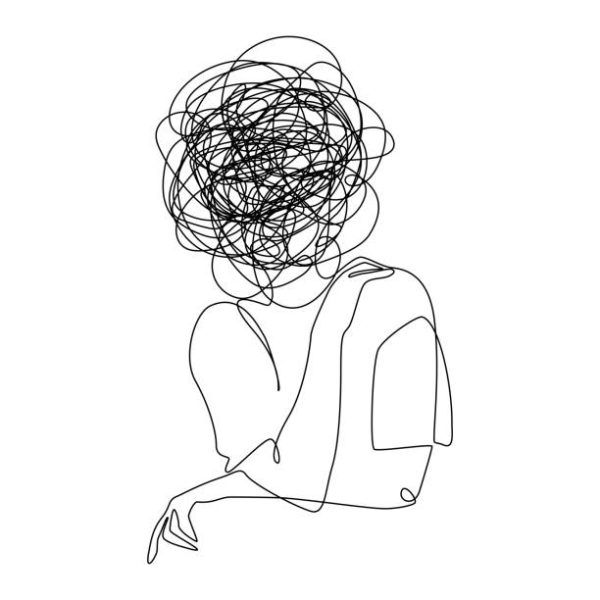

Coping With Anxiety Through Addiction

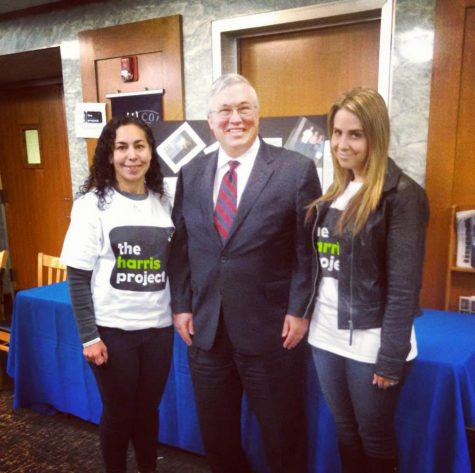

The Harris Project Lectures Students About Dealing With Mental Health Challenges Via Substance Abuse

Stephanie Marquesano shared her message of tragedy and loss to 20 students in Hudson Hall’s conference room on April 14 in an attempt to save those suffering from a disorder which took her son’s life.

It was that journey that began the only nonprofit co-occurring disorder organization in the country: The Harris Project.

Harris Blake Marquesano was a caring, loving friend, brother and son.

“He had a twinkle in his eye and a smile that would light up the room,” his mother, Stephanie, said.

But if you knew Harris, through his twinkled eyes and smile, you’d see there was so much more to him.

Harris suffered from COD or Co-Occurring Disorders, which is the combination of one or more mental health challenges and substance abuse.

Research suggests that 60-70 percent of those addicted to substances have COD, and that 9.2 million Americans meet the clinical diagnosis for COD, with anxiety, mood disorder, PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), ADHD (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder), and ODD (oppositional defiant disorder) being the top mental health challenges.

At age three, he was diagnosed with anxiety and began his journey weaving in and out of therapy. In eighth grade, he clouded his brain with fumes of smoke, which his therapist didn’t shame because he thought it was only a phase of experimentation. But when things got bad, they had to find a new therapist because his “couldn’t help him, because there was nothing he could do,” Stephanie claimed.

High school was no cakewalk either. Harris was diagnosed with ADHD, which is when he was first prescribed medicine. He did well on them, but once he began experimenting with drugs, that’s when his life began to truly spin downhill.

“If you’ve got a mental health disorder and you start experimenting, you’re playing Russian Roulette with yourself,” his mother says, referring to young people.

His junior year of high school, he took pills at a party and stopped taking his meds, not realizing that abusing prescription pills would soon take his life.

Harris wasn’t getting the help he needed and in turn resorted to acting out in a way that wasn’t in keeping with his true personality.

People said he wasn’t acting normal, but his mother hated hearing that.

“I don’t like when people use the word normal. What’s normal?” she asked.

Watching her son unravel was more than just hard, but what was worse was how guilty Harris felt for continually putting his parents and sister, Jensyn, through this roller coaster, and pushing them away.

Harris’s guilt showed through his poem to his sister:

My little star ever glowing

So strong, so brave, so raw, so much life

Bluest eyes, endless truth, your face breaks my heart.

Unrelenting and unconditional, my little star ever glowing,

Goosebumps, tears, spine tingling as I write.

My little star somewhere shining so bright,

When the shouts become strong and I see you in pain,

Little pieces of me shatter, but you, you ever glow

And you say I’m the best when I push you away,

You still claim I’m the best.

So I sit, stare, wait, ‘til your cutest face returns, while these seconds tick without you.

I know our light burns

My one and only girl, the emotion

Lump in my throat swells for your blue eyes.

Jensy I love you, ever glowing, always glowing.

**

A year before his death, he had attended two out-patient programs, one short term mental health in-patient program and four substance abuse in-patient programs.

“Regardless of what rehabilitation programs promise, the treatment model is almost always the same: abstinence from drugs, group therapy, minimal face time with psychiatrists and psychologists, and ultimately discharge from the program.”

But all of these programs were missing one key element: integration. They needed a comprehensive treatment plan with mental health and substance abuse.

“Without this integration, these programs will continue to fail,” Stephanie claims.

“They never talked about the link between the two.”

Because of this, Harris could never be part of the twelve percent of rehabilitation success stories.

On Wednesday, Oct. 23, 2013, 19 year-old Harris lost his life to an overdose.

“One day soon after, I was alone at home. Jensyn wanted to get back to school, so I walked around and started screaming because I didn’t know what else to do. I yelled, ‘Just give me a sign!’” Stephanie said, her voice shaking as her mind re-winded back to that dreadful day.

She walked back into her house and accidentally found a poem Harris had addressed to her:

The things you provided

I took and I took

With greed and selfish tendency

I took and I took

When you warned me of danger

I gave you my back

So then you showed me and gave my life a second chance to re-track

When I stayed up all night

It was your hand on my hand

With a maternal embrace you gave me the power to live on and wake up

Head and body held high

Then I strayed and I strayed

Until you almost lost sight

But you never gave up

No you showed more care than ever before

So now I cry and I cry

But my head remaining high,

No substance besides you can ever be used to comfort this very fragile but very loving yet self-absorbed soul.

I love you mom and if I could take all your pain I would say my dreams have come true, Because the worst that I’ve done is hurting you.

After reading that message, Stephanie found clarity. She knew that she was on the right track with The Harris Project.

The Harris Project became her source of comfort because she strongly believes that “knowledge is power.”

“I speak to high school and college students because you have the power over your own minds,” she tells the Mercy students.

The Harris Project offers an eight hour certification course on Youth Mental Health First Aid (YMHFA). This aid introduces common mental health challenges for youth, and teaches a five step action plan for how to help young people in both crisis and non-crisis situations along with building an understanding of the importance of early intervention.

Mercy College currently offers leading expertise in co-occurring disorders and education, and roughly 120 students are currently trained on campus to deal with such extremities.

“Knowing people are interested in helping makes me feel that I’m already making a difference,” Stephanie said.

That is the goal of The Harris Project: to be the voice of those with COD and bring this disease out of the shadows and into the light.

“We share Harris’s story with you because he would want us to. It won’t bring him back, but we have the opportunity to change the outlook and prognosis for millions.”

Laine Griffin is from the one and only Washington D.C. and is a journalism major at Mercy College. Her hobbies range from playing sports, bartending, spending...