Adjuncts Seek Higher Pay, Benefit Options In May Negotiations Meeting

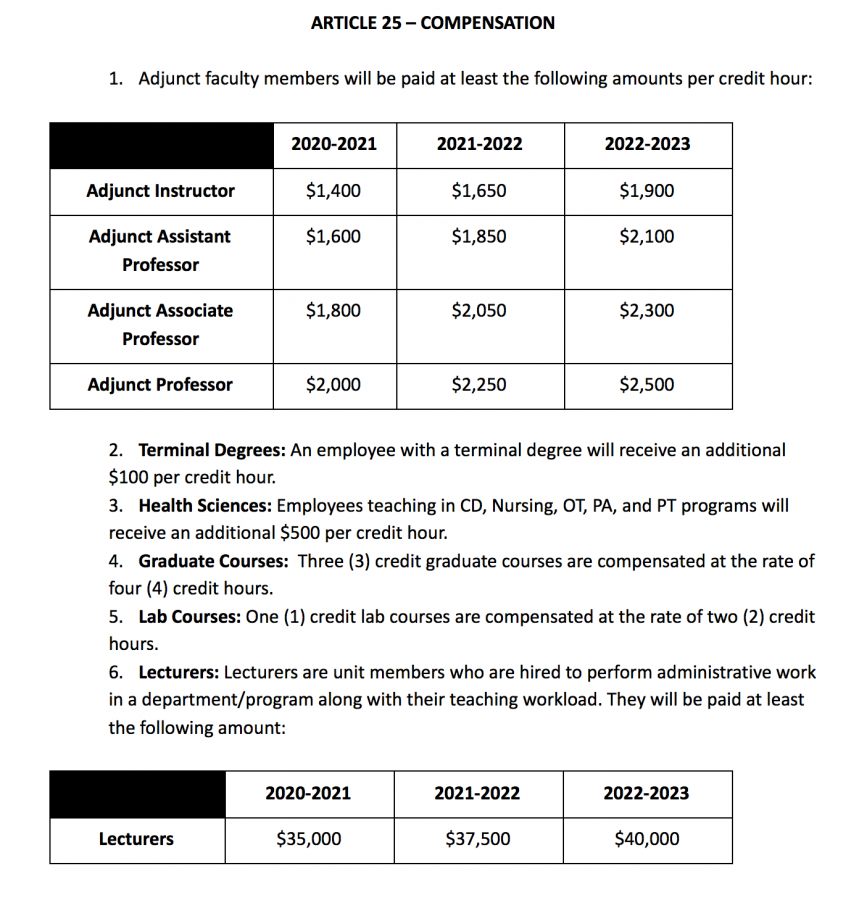

Adjunct representatives are continuing negotiations with Mercy administration in an effort to more than double their salary per course over the next three years, improve job security, earn tuition remission, and have an option to buy into the faculty healthcare plan.

Adjuncts also would like to have a voice in campus decision-making because right now they are excluded from the Faculty Senate and most working committees, they stated.

Upon unionizing two years ago, the adjuncts increased their salary from roughly $2,000 to $3,000 per class. In the new round of negotiations, the adjuncts claim that Mercy has not responded to their recent requests during the last 19 negotiation sessions but will meet in early May.

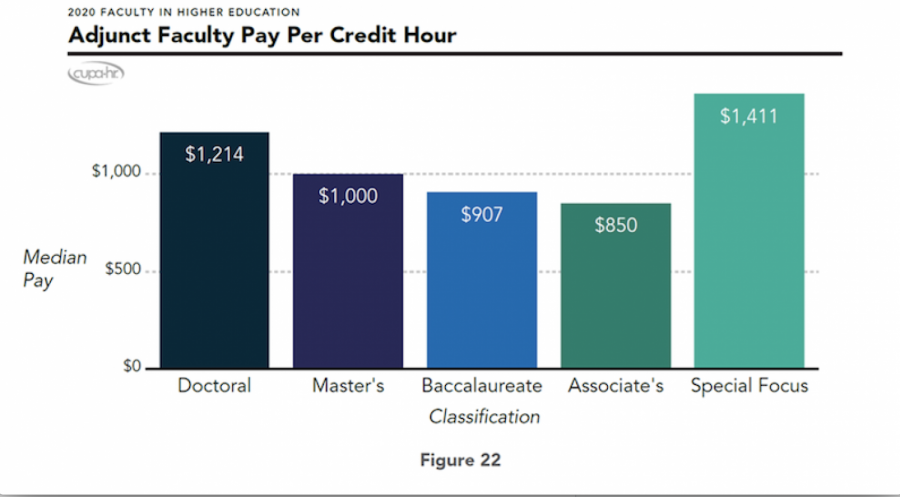

“We are looking for an increase per credit. Regardless of rank, we are all making $1,000 a credit. We want to reward those who have served the institution and give adjuncts some stability,” said Prof. Charles Chesnavage, a Ph.D. who teaches religion at Mercy for the past three years.

The financial proposal from the adjuncts states that they are looking to gradually move up their salary to $7,000 per course. The adjuncts state the proposed number is based on the recent negotiations at Fordham University in the Bronx, who is also represented by the same union as the Mercy adjuncts.

Fordham’s tuition ranges from $56,000 to $75,000 for those who reside on campus. Currently, Fordham has 9,399 undergraduate students. Mercy’s tuition ranges from $11,000 to $16,000 with 6,611 undergraduates students.

Laura Plunkett, Director of Public Relation and Community Relations for Mercy College, stated that Mercy is dedicated to ensuring that students have access to affordable education and makes sure that it can provide one of the lowest tuitions of any private college in the region.

“The request for $7,000 per course is not only outside of the norm for institutions of higher education, but it would also have significant budget implications and inevitably lead to tuition increases for Mercy students.”

Plunkett stated that it is not out of the ordinary for the negotiations to be a lengthy process, and that all contacts, but notably first contracts, can take years, citing the example of Pace University and its adjuncts that took four years to work out an agreement.

“Bargaining sessions have continued during our time working remotely this past year–and during this time we have exchanged proposals on over 30 issues and topics, many of which have been memorialized in written and signed tentative agreements. In addition to these agreements, the college continues to seek compromises on certain issues through mutual exchanges of revised counter proposals.”

Prof. Katherine Flaherty, a lecturer in the seminars program, has been with the college since 2011. She stated that tuition has gone up many times over the years yet adjuncts rarely ever saw the benefit of it.

“Student tuition is not commiserate for contingent faculty,” she says. “An increase to a living wage for adjuncts does not correlate with student tuition.”

The previous significant increase for the adjuncts occurred two years ago. It was concurrent with the adjuncts voting to unionize with SEIU Local 200 by a margin of 4-1, and Mercy College partnering with the College of New Rochelle after the latter announced it was closing down. Mercy assisted those students in finishing their degrees with College of New Rochelle adjuncts, who were already earning about $3,000 per class.

Plunkett stated that by increasing enrollment the college’s enrollment by 2,000 students, Mercy needed to quickly bring adjunct faculty salaries up to par with CRN faculty salaries.

“In doing so, it brought Mercy up to parity with similar institutions in the area as well.”

Yet most adjuncts feel it is not enough.

“I work three jobs and at the most, I’ve had six,” said Flaherty. “Those extra jobs are more time adjuncts cannot invest in students or to Mercy College. That would be more time to focus on research and course content. We wanted not just more money, but a more equitable system and benefits alike.”

“Despite having a Ph.D., I know some of my students are making more than me,” said Chesnavage.

Patricia Meravy is an adjunct instructor in the English department for over 25 years. She wants the college to recognize the worth of everyone involved.

“We want to continue to make a significant and constructive contribution to the college, such as increase the graduation rate, but we need support to make these changes.”

Adjuncts have felt uncomfortable negotiating in person due to COVID-19, they claimed, and also because they have no health benefits.

Currently, they are not offered healthcare benefits or retirement benefits.

“So if you put together a low salary and no benefits, you’re in trouble if you get sick,” said Chesnavage.

According to the United States Government Accountability Office (GAO), a study from 2017 stated that 35 percent of part-time college instructors in the nation have the option of benefits while 78 percent of full-time instructors have the option.

The adjuncts request for health benefits is as followed:

- Employees who teach three classes per academic year shall be eligible for medical, life, and disability coverage.

- Employees who teach less than three courses per academic year shall be eligible for dental, life, and vision.

- Employees who reach less than that can receive a $1,000 medical stipend per class.

Adjuncts would also like the opportunity to buy into the plan that is currently on campus available to full-time faculty.

Retirement benefits are also something that is not offered to the adjuncts by Mercy College. The adjuncts are asking for 10 percent of each paycheck to be matched by Mercy into the 403(b) Basic Retirement Plan.

The adjuncts asked for job security as well, a complicated task as enrollment fluctuates every academic year, determining how many adjuncts are needed. Chesnavage agreed that a decline in enrollment could potentially affect the adjuncts’ job security, but adds that those should then be compensated for it.

“It (low enrollment) could lead to fewer adjuncts being hired. Adjuncts have been scheduled to teach but then find out that some of the courses they prepared for will no longer be taught, and some of them are not even told.”

By offering job security, adjuncts would be able to be compensated when courses are removed but preparation took place, he added.

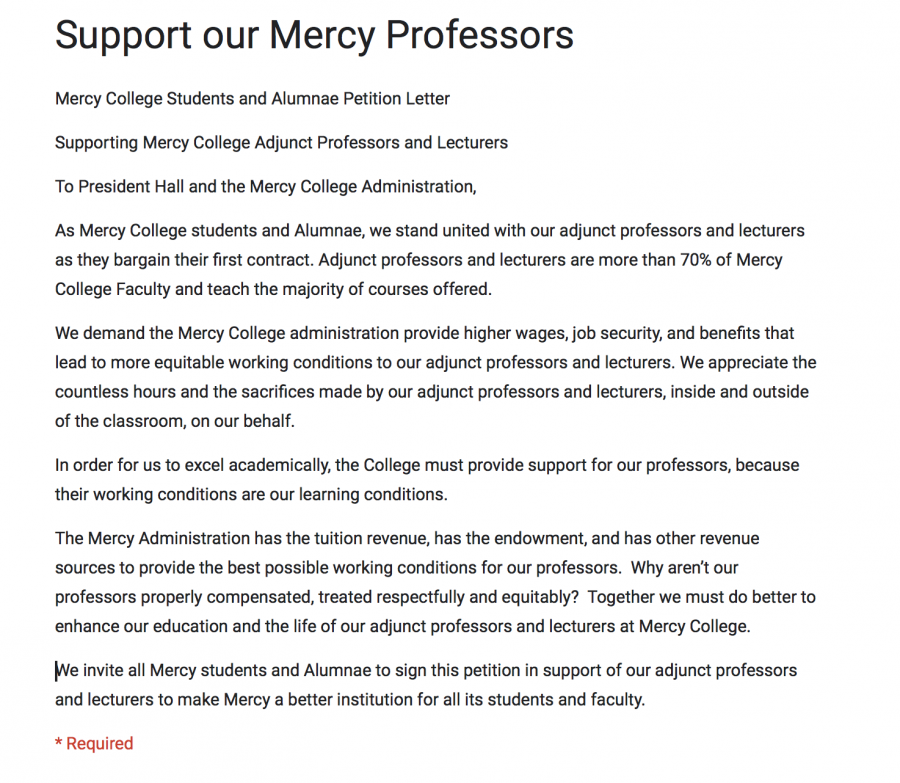

According to the adjuncts, 75 percent of classes at Mercy are taught by roughly 600 adjuncts employed by Mercy. This point was provided by the Letter of Petition that circulated around campus digitally last month, targeting students and alumnae.

“We invite all Mercy students and alumnae to sign this petition in support of our adjunct professors and lecturers to make Mercy a better institution for all its students and faculty,” the letter read.

The adjuncts also claim Mercy makes $50,000 in profit per course offered. This number is based on their claim that each course has 20 students who are each paying $2,500 per course.

Plunkett states that the money from Mercy student tuition goes to many different services, activities, and resources at the college.

“These not only include costs associated with offering each class but also include expenses directly related to the classroom experience, as well as expenses related to supporting students’ academic experience and expenses related to operational costs of the college.”

Chesnavage claims that the college has used stall tactics in its negotiations. He stated that the adjunct union submitted its economic proposals in February and has yet to have had a response.

“It’s called negotiation fatigue,” he said. “You wear people out.”

Prof. Caroline Curvan has been teaching at the college since 2016. In 2020, she was awarded the Teaching Excellence Award for Part-time Faculty in 2020. She is hoping for these issues to be resolved and feels the sooner they are, the better for all.

“We are hopeful that they will propose counters to us at our next meeting. We can only hope administration starts paying attention and negotiating in good faith,” she said.

Flaherty stated that the adjuncts had just as many of the challenges that the students had during the pandemic such as a lack of reliable computers and unstable wifi connections. Chesnavage added that the adjuncts would have liked better IT training for the reopening after the pandemic. He claims that adjuncts at Westchester Community College were given a modest payment of IT training and that the Mercy adjuncts were denied that request.

Plunkett stated that Mercy College has long offered adjunct faculty training opportunities through its Center for Teaching and Learning (CLT) and that any faculty teaching online is required to take a basic Blackboard training course and has opportunities for related courses. That process greatly increased after the pandemic, she said.

“In March 2020, the college had completed more than 163 Blackboard training sessions. By the start of April, at least 73 percent of faculty completed at least one Blackboard Training. By Sept. 16, 2020, 86 parent of our faculty completed one or more Blackboard Training Session. ”

Plunkett added that Mercy invested in Zoom cameras in classrooms so all could meet synchronous, and that IT was available in classrooms to make sure all was running smooth.

Curvan said that there were a lot of challenges to transferring an in-person class to online teaching. “It is not as simple as turning on a camera and talking. We had to redo the entire curriculum. We had very little support to do that.”

“We were not included in the process in how the prepping would take place or about safety precautions,” added Meravy. “We had been invited to a meeting, after the fact.”

Chesnavage stated that adjuncts are not happy with how Mercy has spent some of its funds in what he refers to as “exploited labor.” The Mercy College endowment is estimated at nearly $250 million and received COVID-19 funds. He argues that Mercy purchased the Manhattan campus a few years ago, runs television commercials, and hires an “expensive” law firms to represent itself.

Mercy College has been occupying space in the same building in Manhattan for more than 20 years, said Plunkett. “At the time our lease was coming to an end, the college was able to renegotiate at very favorable terms with new landlords who had recently purchased the property.”

Retired full-time faculty member and now adjunct, Prof. Art Lerman, has many thoughts on the concept of “exploited labor.” Lerman was hired by Mercy in 1981 and was full-time until 2008.

“I was a part of the problem,” Lerman stated when speaking about his time as department head. As a department head, he had the job of hiring adjuncts. Lerman felt morally bothered by his background but now he is very happy to be working for the adjuncts to help get them what they need.

“This is not even a national problem but a worldwide problem. Employers are less and less committed to full-time employment, good salaries, and healthcare. Retirement benefits have taken a hit in the United States, this issue has been around for a long time.”

He felt there was pressure for the adjuncts to negotiate in person, as the adjuncts wanted to continue to meet through Zoom.

“It may be too dangerous and early for that,” he said.

Chesnavage hopes a meeting in May will lead to communication between the two.

“After becoming unionized and 19 negotiation sessions, we are 0-3. They have not responded. They have not offered us anything significant other than benefits already included.”

Alexis Lynch is currently a senior at Mercy College. At Mercy, Alexis is a Media Studies major with a focus in Journalism. She has gained experience that...

James Tiedemann graduated from Mercy College in the May of 2022. He transferred there after graduating from SUNY Orange with his Associate's Degree in...