Dory Finds Herself A Star After Nemo Sequel

Before walking into Finding Dory, I couldn’t help but wonder, “Do we need this? Is this necessary?” Disney marketing executives would say yes, Disney stockholders would say yes, and most importantly the parents of a little girl with a disability would say yes. Finding Dory exists as the product of the Disney/Pixar certifiably perfected formula for a sequel, but it doesn’t sacrifice the integrity of telling a good story in the process.

Dory has a rather disappointingly simple plot: Dory (Ellen DeGeneres) finally remembers that she has a family and seeks to return home. All of the major players are back, including Marlin (Albert Brooks) and Nemo (Hayden Rolence), and we meet some new ocean creatures along the way: Destiny (Kaitlin Olson), Bailey (Ty Burrell), Fluke (Idris Elba in his third voice role this year), and plenty others. Although we are 13 years past Finding Nemo, Dory’s story picks up one year after she meets her neurotic neighborhood clown fish, Marlin.

It’s become a well established truth that Pixar films are expected to deliver on three specific things: stunning visuals, inventive storytelling, and emotional poignancy. In term of animated visuals, Pixar remains in a league of its own. Directors Andrew Stanton and Angus MacLane scale Finding Dory down from its predecessor; so rather than exploring the entire ocean, most of the film takes place at a Marine Life Aquarium which happens to be safeguarded by the sci-fi world’s favorite female badass in a divine voice role. As a result, the “camera” is tighter on the freckled faced Dory and her cohorts, and the scenes are more intricately choreographed. One scene is particular finds Dory and a septapus called Hank (a wonderfully gruffy Ed O’Neill) navigating a Poking Pool (where kids can harass the sea life by poking their fingers in the water), and watching the royal blue Dory quickly swim through a minefield of kiddy fingers is a spectacle.

If there were one area for improvement in Finding Dory, it’d be it’s unfortunately straightforward plot. After being asked by a younger fish about her family, Dory logically deduces – Dory’s consistent application of logic is delightfully refreshing, I might add – that at one point she had one, but she can’t remember who they are or where she’s from. The film then makes an effective use of flashbacks to reference the journey Dory’s on now with tidbits of memories from her childhood. Dory’s strange idiosyncrasies from Finding Nemo are also explored more deeply, most of which were used as coping mechanisms or helpful tools for her particular disability. As effective and affecting each of these pieces are, they don’t completely hide the shortcomings of the plot. It’s not that Finding Dory is overly complicated or utterly boring. It’s that with Pixar, we’ve come to expect innovation like the mostly silent Wall-E or the hero-caper moving pieces in The Incredibles, and Dory doesn’t quite reach those narrative heights.

In a film where finding you parents, your home, and yourself are the main goals, it’s more than fair to assume that huge emotional moments will occur along the way. Finding Dory excels are here, and in no small part due to Ellen DeGeneres’ voice performance. She understands Dory’s ticks and quirks, she obviously can sell a joke (you don’t become the top rated daytime talk show this side of Oprah without that), and she perfectly conveys Dory’s stream-of-consciousness style dialogue. Dory also has the luxury of having Diane Keaton and Eugene Levy as the perfectly empathetic and encouraging parents of child who suffers from short term memory loss. And each moment the three share on screen is Finding Dory at its emotional peaks.

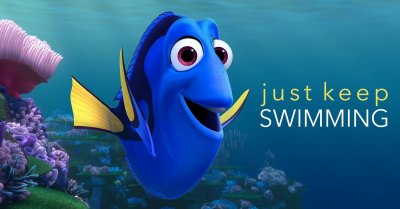

Even more so than Ellen, however, is how the film portrays fish with disabilities navigating the ocean. Each of the characters faces an obstacle – Dory’s short term memory, Nemo’s tiny fin, Hank’s lost tentacle, Destiny’s near blindness and, to an extent, Marlin’s crippling anxiety – and yet, none of them are ever treated as anything less than whole. Dory’s relentless optimism, and her “just keep swimming” mantra, empowers the others to redefine what they’ve been told is a weakness and turn it into a strength. And while this is a lesson anyone can learn from, it’s especially powerful for the kids in the audience who don’t see themselves or their disabilities on screen as anything other than a punchline or a sob story.

Rather than expanding the Finding Nemo universe, Finding Dory takes an alternative approach to sequels and zeroes on a one character. Dory dialogues, then monologues, then dialogues again through funny, touching adventures and we can’t help but get swept up in her life. Going smaller paid off big for the happy Disney marketing heads and stockholders, but the film stood on it’s own as something that feels essential. It feels necessary. If you can only remember the last 5 minutes of your life, sometimes the only option is to do what makes you happy right away. So when I left the theatre, I couldn’t help but wonder, “What would Dory do?”