Learning in the Age of Loneliness

A survivor of the Virginia Tech shooting, Dr. Robert Murray has felt this pain before.

Seung-Hui Cho, in a little under three hours, would kill 33 and be responsible for another 23 injuries on April 16, 2007. Before police could confront the undergraduate Virginia Tech student, he would shoot himself in the skull, killing himself.

Dr. Robert Murray, who is now the Chair of the Humanities Department and an Assistant Professor at Mercy College, remembers that day vividly. He was a Hokie.

Thirteen years to the day of what was the deadliest shooting by a lone gunman in American history for nearly a decade, The Impact was able to speak with him about his world as a student then versus his reality now, amidst a global pandemic.

“I lived in graduate student housing so because I went to Tech on a lark, I didn’t have time to find an apartment so I lived on campus. Right after the massacre had occurred, I was waking up to chaos outside of my window.”

While one may take alert system tests for granted, Murray cited this as a prime piece of criticism toward Virginia Tech. Beginning at around 7:15 a.m., Cho would kill two students before returning to his room, and nearly two-and-a-half hours later, at 9:40 a.m., he would begin shooting within VT’s Norris Hall.

For the then-graduate student and his peers, the feeling of reality slowly dripped onto them.

“There are confusing messages circulating. You hear that there’s a shooting, but nobody knew how bad it was,” elaborated Murray. “I remember when the local news crews came to report the story first. We were all together from my floor watching this on TV, and we realized that this was a live broadcast. If you stuck your head out the door and looked slightly to the left or right, you would be staring at this TV crew live, and that was the most unsettling image.”

But unlike 2020, where information is as accessible as one may want it to be, there was a time where hearsay was the primary source for the students of VT. It wasn’t until the backtracking of names, where they had last been seen, where they were supposed to be, messages to them, and all other means of retracing someone else’s footsteps, until realizing what was the worst-case scenario for a friend or colleague: that they were in Norris Hall that morning.

“I was there when one friend discovered most of his thesis committee was dead. I was walking in the hallway when Matthew Gwaltney’s parents were cleaning out his room and his mother told me and my small group of friends, ‘I’m sorry. This must be hard for you.’ Luckily, someone else mustered a response because I was actually incapable of making a sound. I had been elected President of the History Graduate Student Association only one week before, so my first official act as President of the HGSA was to send flowers to the parents of Leslie Sherman, a history major who had been killed.”

“I sat in a florist shop in Blacksburg, Virginia, and again could not find any words. I think I just said, “Our thoughts and prayers are with you.’”

In a similar vein to Mercy College, Virginia Tech announced an immediate cancellation of classes for the rest of the week. Although Murray chose to not go back home to his native Kentucky, citing that he didn’t want to hear from his parents and “why I should never go back to college again.”

But what eventually drove him away from VT wasn’t the news coverage, sadness, or anything else. It was the smell.

“Even though you were just walking down the sidewalk, far away from where it happened, it smelled like I had opened up a container of bleach, and if I just had my nose over the opening.”

It made it an easy decision.

“Everything had happened on Monday, so it was only Wednesday when I just said, ‘Okay, I have to get out of here.’”

But also in a similar vein to Mercy, the academic world eventually resumed for the students in Blacksburg, Virginia. With a policy of choosing to “freeze” one’s grade for the rest of the semester (which was about three weeks), the remaining time of that semester was spent in the arms of others.

Whether it be in classrooms, cafes, or at the house of Murray’s history graduate advisor, the peers and friends of his community could come together to mourn. The difference, this lack of humanity in a literal and metaphorical sense, is what separates the shooting from the ongoing COVID-19 crisis. And in the opinion of Murray, it makes this current situation worse.

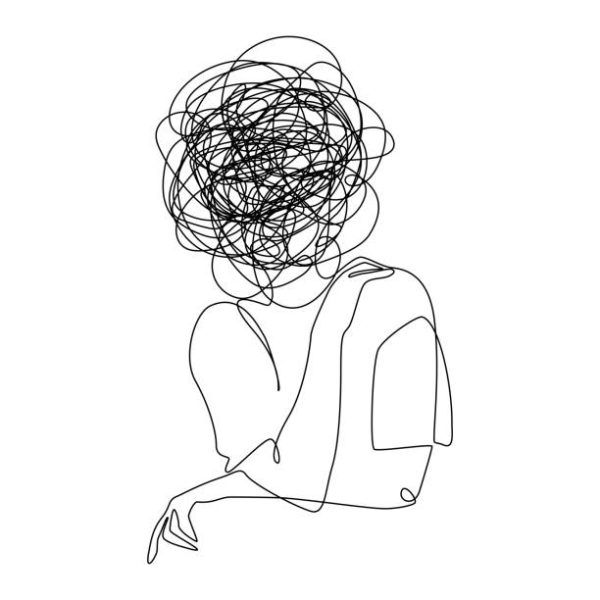

“That’s the thing that’s giving me the tangles; the echoes from this moment is that we only had to survive a few weeks at Virginia Tech, which I suspect was one decision to return to the campus. Now, we have a sheltering order going to May 15, at least. Now, every decision you make is life and death.”

Even something as necessary as grabbing a cup of coffee or going grocery shopping is now a literal sacrifice. “We can Zoom. We can FaceTime. We can do these things on-the-fly, moving the entire semester online. Not to say that we’ve done it seamlessly and efficiently for everyone, but it’s really not so fun experiencing each other’s phone issues or seeing people have a hard time.”

That feeling of being trapped makes all that’s going around that much worse, Murray feels, despite the accessibility many have to WiFi, it’ll never bridge the gap.

“That’s one thing I keep about that Tech experience is knowing how important it was to sit in a seminar room and talk. That was processing, and that’s the one thing we can’t do now. Video chatting is not the same. It’ll never be the same.”

That, in Murray’s eyes, is the cruelest part. What makes the age of loneliness so much worse is the ever-present reminder of what once was. He claims that a Zoom or Collaborate meeting, while better than nothing, is only an elephant in the room.

The potential for academic greatness, discussion, and other celebration within the field of his students is a constant disappointment, too.

“I saw the trajectory of where my students were going. We would have had fantastic conversations that came from what we were building this semester. Even though we have a mechanism for conversation, it’s just not the same as being in the room, where you can read body language, you know who wants to talk, who’s fidgeting in their seat because they want to go next, and you just don’t have any of that.”

With the recent announcement of students being able to declare their intention to either go toward credit earned/no credit (pass/fail,) this has not only put more pressure on the Mercy community, because of its May 7 deadline, but it opens up an even scarier reality: what happens after the semester is over? Can everyone heal like the Hokies once healed?

“At least right now I have the students until May 13, and as much as I’m trying to see if this continues much beyond that then I then I really have no one else to talk to regularly,” conveyed Murray. “So that’s a sobering thought. I haven’t really come to grips with. It’s hard to keep track of what I need to get done for tomorrow and also what needs to get done in two weeks, and what needs to be done in a month because time just feels flat and indecipherable right now.”

Steven Keehner was the Managing Editor of the greatest publication on the Hudson.

Hailing from the mediocre Town of Oyster Bay, New York, he enjoys...