PACT Mentor Gets Education By Coaching Female Inmates

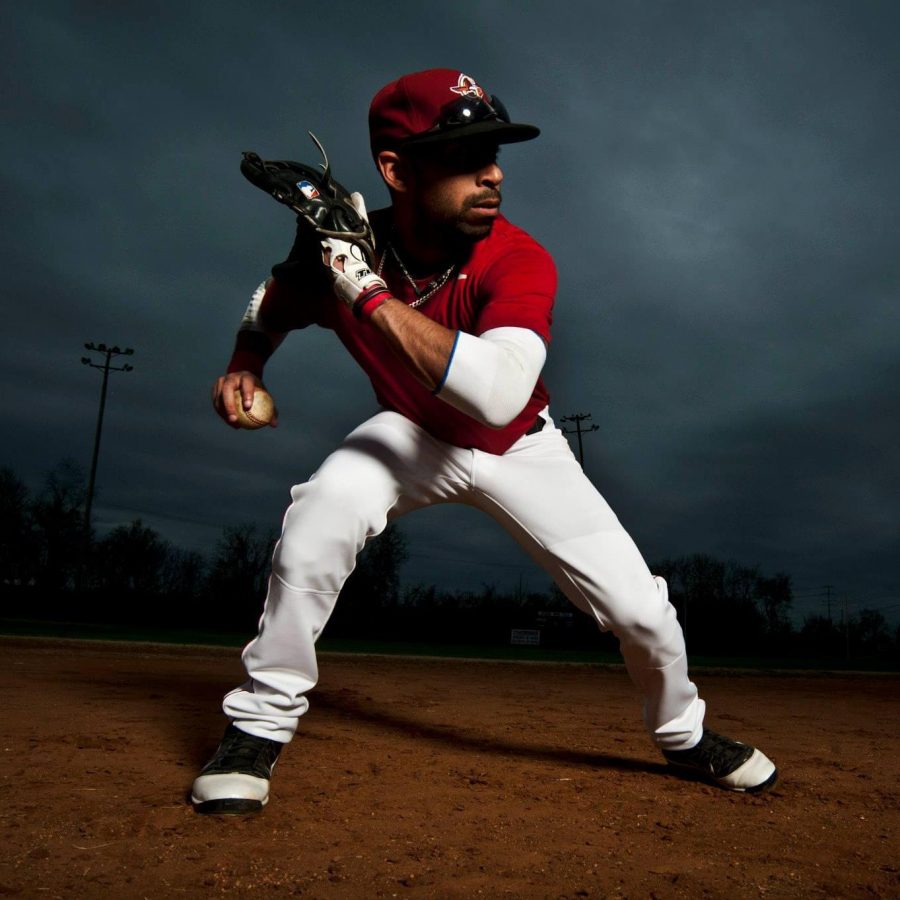

On a warm, summer day in July, Mercy College’s Runie Mensche walked on to the field to meet his new softball team. In the distance, he saw his players waiting for him. Standing side by side, they all wore red shirts and gray bottoms.

The position was unlike any other for Mensche, because not only was he coaching an all-women’s team, but they were inmates at the New Hampshire State Prison.

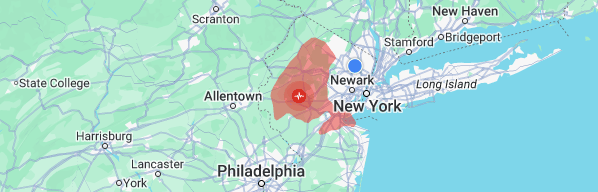

The New Hampshire State Prison for Women (NHCFW) is located in the town of Goffstown. It’s the only state prison for women in the state. Compared to other facilities in neighboring towns, it’s relatively small. The maximum population is 224, according to the official New Hampshire government website, nh.gov.

Mensche is a Manhattan PACT mentor for the School of Liberal Arts and Natural Sciences and spent the past summer teaching incarcerated women how to master the game of softball. It wasn’t a typical job, and usually not the response expected to the question, “What did you do this summer?”

From that moment on, Mensche had an interesting story to tell to anyone who had asked the question.

Prior to working at Mercy, Menshe was a Hall Director at St. Anselm College at Western New Hampshire. One of his goals was to become a coach for a sports team. His colleague at St. Anselm knew of his love for sports, especially baseball, and asked if he would assist him in coaching during the summer.

When approached with the idea, Mensche never imagined his first coaching job to be at a prison. Given that he never stepped foot in one, he didn’t know what to expect. Despite his reservations, he looked at the opportunity as a stepping stone in his goal of coaching professionally one day.

“I’ve never done any formal coaching before but this would be a very good experience because I wanted to coach baseball,” Mensche said.

The following week, Mensche went to the New Hampshire Department of Corrections to fill out paperwork and to get a background check. He passed the check and had to attend meetings to learn what to do and not do when interacting with the inmates. After two days of training, Mensche was ready to meet the team.

Mensche entered the prison and was met by guards. He removed any metal objects from his pockets such as his keys and cellphone. He walked through the metal detectors and was cleared to proceed. He wasn’t allowed to bring any sports equipment. The prison supplied reasonable ones for the inmates to use. To his left, he saw classrooms and to his right a laundry room. Mensche learned that the women worked in different areas of the prison. They’re required to start their day at 8 a.m. and aren’t allowed to take naps. There is no time for extracurricular activities. This is all an effort to keep them busy and focused.

Mensche stood in front of the doors leading to the field. He waited for the guards to buzz him in so he could enter. From one checkpoint to another, the guards have to grant permission first. He walked through the doors and stood on the field. Mensche recognized that the field “wasn’t Yankee stadium” in size. Mensche’s colleague approached him on the field and they both waited to meet the inmates. A group of thirty-five women walked onto the grassy field. The women and Mensche were face to face. His colleague led the meeting by introducing Mensche as the assistant coach. Mensche wasn’t nervous when the inmates approached them; rather he was excited to get started. After everyone became acquainted, it was time to play ball.

“Let’s stretch, let’s throw. Let’s work on this drill. Outfielders over here,” Mensche said to the inmates.

Feeling instantly comfortable in his assisting role, Mensche demonstrated to the women how to properly throw a softball for the most effect. They watched and then repeated the technique. The inmates were eager to learn about the sport and finally get the chance to do something fun.

“What a regular person would see as no big deal, they appreciated. They don’t get a chance on a regular basis because they lost that privilege. But now, for an hour and half to two hours, they get to be themselves and better themselves through the game,” Mensche said.

While coaching, one of the women of the team stood out. Jessica (last name withheld) played softball as if she had been playing it for years. Her athletic abilities to dominate the field were not by coincidence. Jessica was a former college softball pitcher. Mensche was happy when he learned that Jessica had a love for sports, but soon came the sadness. One bad decision cost Jessica her entire future.

“She was a kind-hearted, good person. How did she end up being here?” Mensche thought.

Even though Jessica was incarcerated, she now had a chance to relive her glory days she has as a student athlete.

“This is a way to make a difference in their lives, but there is significance in normalcy. They step out of themselves; they step onto the field, and they just play. It taught them structure, it taught them teamwork, and it taught them how to appreciate the little things in life,” Mensche said.

After weeks of practicing, the first game of the season approached. The women of the prison played against Mensche’s colleagues at St. Anselm. All the players approached the field. The inmates used the skills they learned and were leading in the game. Mensche looked at his team in amazement.

In the final seconds of the game, the teams were neck and neck. One final pitch from the inmates sealed the deal, and they won the game. They couldn’t believe that they did. The women were screaming and jumping with joy. Tears rolled down some of their faces. Mensche was proud of his team.

“This is something that they looked forward to during the course of the week, so you better believe they would take full advantage of it” Mensche said.

The next couple of weeks were filled with practicing twice a week and playing games against local churches, lawyers, and the inmates favorite, the security guards. While in the midst of the season, Mensche got the call to become a PACT mentor. He was excited for this new opportunity, but he would have to resign from coaching the inmates. When he told the women he would be leaving early, they were sad. The women had grown to love softball because of Mensche’s coaching skills and now they had to finish the season without him. On Mensche’s last day, the team played in his honor. It meant a lot to Mensche that they did that for him.

From the beginning, Mensche didn’t judge the women of the New Hampshire State Prison. He viewed them with the same respect he would have for any student he encountered. When Mensche signed up to coach the women of the prison, he didn’t know it would turn out to be such a rewarding experience. Although it wasn’t the summer he planned for, it turned out to be one he would never forget.

In July, Mensche started as a PACT mentor at the Manhattan campus. He welcomed his students and were ready to assist them with their academic careers. Mensche often reflects om his summer with the women at the facility.

“Sometimes people think we need resources to make a difference, but your actions and your words can do that for you.”

Shantal Marshall is from Brooklyn, New York and majors in journalism at Mercy College. Her hobbies include reading O magazine, listening to music, and...