Mercy College Hosts “Education & Equity, Inside & Out” To Celebrate Incarcerated Students

“I was wondering if I had a life to live,” says Judith Clark. who served 38 hears in prison for her role as a getaway driver for a robbery in New York.

She was sentenced to a term of 75 years to life.

As a new mother, she was a in a dark and lonely place. She was fortunate to be enrolled in a college degree program. She was in a philosophy class when it all finally clicked.

The professor told the students they had free will when it came to their assignments. It was the same professor who gave her a quote that she would carry for a lifetime.

He said to her, “Even though you don’t have the freedom to choose your circumstances, you have a choice of how to act when faced with those circumstances.”

Those words resonated with her. “I realized that even though I no longer had control over many aspects of my life, I can choose how I can react to my situations and how to help others.”

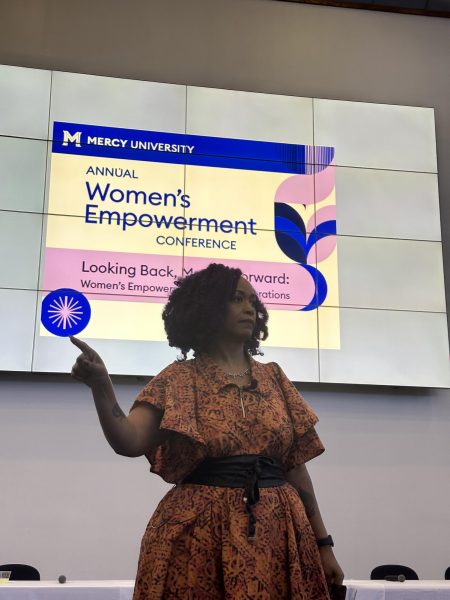

Clark’s philosophy on life was changed forever, as were many others who spoke at the event titled, Education & Equity, Inside & Out. The event is part of the Deans’ Series on Diversity and Inclusion, presented by the School of Liberal Arts and the Center for Social and Criminal Justice at the School of Social and Behavioral Sciences, in collaboration with Hudson Link for Higher Education in Prison.

The Zoom webinar took place on Feb. 18 and was hosted by Seminars professor, Austin Dacey The featured four speakers including Clark, Roslyn Smith and Jermaine Archer, all who were formally incarcerated and received degrees at Mercy College via Hudson Link. Also speaking was Dr. Mary Cuadrado, a criminal justice professor at Mercy.

Founded in 1998, Hudson Link works in collaboration with different colleges and provides college education for incarcerated men and women. The program has led to inmates to have better support and outlooks on life and possible reentry to society. Since the 1970s, Mercy College has provided college tuition aid and education to inmates and was one of 70 colleges offering programs to different prisons in 1990s. However, after 1990’s crime bill was released and Pell, which provided aid for prisoners was terminated in 1994 (later reinstated), many inmates were left fighting for education in and out of the prison system.

“Higher education would not have survived if not for the resilient behavior of incarcerated or formerly incarcerated students,” says Dacey.

Clark received her college degree in 1990 at Mercy College and studied Psychology. Since her release, she found different programs to help inmates receive their college education. Mercy College was not the first time she had taken college classes as she was enrolled at the University of Chicago, but was expelled for sit ins in 1969. Following her expulsion, she was involved in many crimes and “rebeled out” on different occasions, which then lead to her arrest later on.

“I had a 1-year-old child when I went in. I was in a low place.”

When she was at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, she realized there was a college program offered and she enrolled. It saved her life in many aspects.

The year after she graduated, Pell was rescinded and with no public funding, many colleges pulled out of teaching the incarcerated population. She reached out to Marymount Manhattan College and formed a coalition with colleges, women incarcerated, sponsors and in a year, began running college programs in prisons in Westchester.

“We wanted to bring together a core of people who began to see themselves as movers and shakers and realize that knowledge is power.”

Roslyn Smith graduated from Mercy College through Hudson Link in 1993 and is currently one of the founders of V Day, an organization which strives to end violence against women. She went to prison when she was 17-years-old for the homicide of an elderly couple, and was sentenced to 50 years to life. She takes full responsibility for her actions and continues to takes strides to try to make up for her actions.

First the first nine years of her sentence, she rebelled and had a difficult time adjusting.

“I asked myself, ‘Why should I get an education?’ I figured I was going to die here (in prison).”

Smith didn’t receive a high school diploma or GED before her incarceration so she completed her GED after her first year. Then after the ninth year, she decided to enroll in the college education program but received so many absences she failed all her courses. She decided to re-enroll in the program and this time, decided to take her classes and her life more seriously.

“If this is going to be my life, I’m going to do more with it,” said Smith, who admitted to doing a horrible thing. “I am going to do the best I can to prevent someone else from doing the same thing.”

The program provided more than a degree for her, it allowed her to pursue therapeutic resources to help her deal with trauma brought from the crime she committed and then helped other people around her. Then in 1993, she received her bachelor’s degree and worked as an academic aid at Mercy College and helped students with entry exams and tutoring.

“The view I have now changed because of the education I received in prison… it helped me be the woman I am now.”

Jermaine Archer spent 22 years in prison for murder, a crime he maintains his innocence. He graduated from Mercy College’s Hudson Link program in 2013 in Sing Sing and was released from prison in September 2020. He spent the first two years of his sentence in solitary confinement and was extremely angry that he was forced away from his children and life. After years of anger, he realized that he needed to reclaim his life and do something positive with it.

“Something clicked,” says Archer. “I realized that this is all my life is now and I need to find a way to get it back.”

After his 2013 graduation, he received his master’s the following year and his paralegal degree the year after.

When the COVID-19 pandemic began, it hit prison system extremely hard and in his opinion, will forever change the way education is received behind bars. At first, the government temporarily limited class sizes within prison education classes, which was then followed by reducing the number of materials that could be brought in by professors. Eventually all classes within the prisons were shut down “temporarily.” Prisons are used to temporary bans that remains at a standstill. One example is the temporary tea ban placed in 2014 due to the K2 epidemic, which is still in effect today.

All inmate students were allowed to study in their cells and allowed to go to the community lab to submit their assignments, but many inmates who were excited about receiving a college education were losing motivation to continue. In addition, many of the prisons libraries had outdated materials, and many books had torn or missing pages or were not present. For years prior to COVID-19, prison advocates were vouching for updated technology equipment and applications such as Zoom and were denied, but COVID-19 made the discussion prominent again outside the walls of prisons. Then once family visits were suspended and classes were halted due to the pandemic, many inmates turned to anything to get them through.

“I knew guys who were motivated [for classes] and when everything stopped… they turned to dangerous drugs.”

One of Archer’s fears is that the COVID-19 pandemic is going to lead to many professors limiting the effort they give to providing good education to inmates. He fears it can lead to many inmates not receiving the best education they could get.

“It’s going to be a watered-down education. They could leave with a degree but not with a college education,” says Archer

Dr. Mary Caurado is very proud of Mercy’s role in the education of inmates.

“We’ve been providing education to inmates before it was cool says,”Cuadrado, who was the final speaker at the event and spent her time vouching for the need to preserve high levels of effort of education during the current pandemic, especially in the prison system.

“I am a talking head on a string and there are many things that are pulling my students attention away,” says Cuadrado.

Today, Pell grants are once again being threatened due to the pandemic and prison advocates are trying to preserve the opportunity for inmates to get a college education.

Clark sees the challenges ahead, but realizes the importance of keeping a program that altered her life and many others for the better.

“Just as it was a struggle to create these programs, there will be a struggle sustaining them.”

Britney Guzman is a Senior at Mercy College. She writes a column called Quali-Tea News where she discusses her love for cats, Taylor Swift and mental...