Congratulations on the New Arrival

The time never seemed right. What was the appropriate setting and time to learn your ancestry?

“Are you upset that you are adopted?”

My dad asked me once as I sat on his lap on an old chair in the living room. What is the proper setting and sitting position to learn at 5 years-old your dad your parents are not where you came you from?

The person you have called your “dada, daddy, dad, and father” is telling you that someone else is and that someone else is your mother. I couldn’t even look at him, because how do you look at someone who changed every hour, day, and year of the rest of your life because he corrected you on what to write in the space for a genealogy and family history school project.

Damn you school for assigned the project.

The fill-in questionnaire asked:

You have any siblings? No.

How many aunts and uncles do you have? Five.

Are you adopted? No.

My dad chimed in from the kitchen a couple feet away from the table in the den I was sitting at.“Matthew you are adopted…”

I can’t for any money offered, threat leveled against me, or any wish a genie could grant, can I remember the exact events and words spoken until I was sitting on my dad’s lap.

I can remember changing my answer, the tears that started in my eyes, and my dad trying to string words together like “Texas,” “Mexican,” and “your mother.” All of this set against a backdrop of confusion no five year old is accustomed to. Maybe it is the numbness that comes with confusion that made it the best backdrop for the one memory I can remember.

It was the day I realized that the color of my skin had etched itself into every fiber of my life from my unknowing at birth to the great unknown I will only come to learn on the last day of my life. It’s the realization you’re different and will be treated differently because of skin tone. It’s a realization every person of color understands and remembers feeling for the first time, but I was going through it alone.

It was those memories that I could not build a dam against. The memories flooding back as I stood at the same table, sixteen years later, spitting into a plastic vial. My spit that I would seal into a pristinely designed box with the words, “Welcome to you.” Welcome to me? Not the first welcome as I’ve met and said goodbye to as many people as I can to know who I am. This 23andMe kit likely the last welcome I will make because I have nowhere else to go to know where I came from.

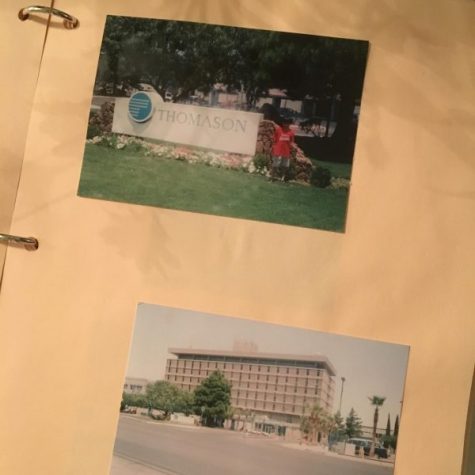

My name is Matthew Miguel Reich and I was born at 1:23 p.m. on Aug. 29, 1996 at Thomason Hospital in El Paso, Texas. I cannot tell you if there were tears of joy or sadness or if pictures were taken of me when I was born. I can’t even tell you what the weather was that day. There is nothing I can tell you about that day.

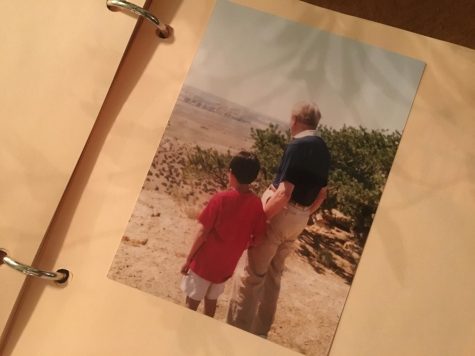

Something, I can tell you is I remember when I was eight years old and I went back to Texas. Before we made the leap across the border into Texas, my dad, grandpa, and I spent the first half of the week in New Mexico. Even though, I was not born in or had ever set foot in the state, until then, I felt I had never been closer to where I came from.  I felt a sensation I can only describe now as a pull towards somewhere beyond the arid rock, sand, and blossoming flowers that peppered the landscape. We stopped on our last day in New Mexico at a reservation high atop a mountain. A journey I remember because my grandpa prolonging the tour group’s time atop the hundred-degree mountain top because of all his questions, I got heat stroke and was taken in by a Native American couple into their home to cool off, and a small clay container I bought for $10 from a woman’s table next to the cliff.

I felt a sensation I can only describe now as a pull towards somewhere beyond the arid rock, sand, and blossoming flowers that peppered the landscape. We stopped on our last day in New Mexico at a reservation high atop a mountain. A journey I remember because my grandpa prolonging the tour group’s time atop the hundred-degree mountain top because of all his questions, I got heat stroke and was taken in by a Native American couple into their home to cool off, and a small clay container I bought for $10 from a woman’s table next to the cliff.

As I was trying to understand the directions of a DNA kit, I thought to myself how I carried a tinge of hope to have a sliver of ancestry of Native American or indigenous peoples.

I think I’ve always been drawn to the cultures of indigenous peoples because I envy their devotion and determination to protect everything that contributes to their identity and culture. I could only wish and hope I had some idea of my own ancestry and heritage to place that admirable devotion in.

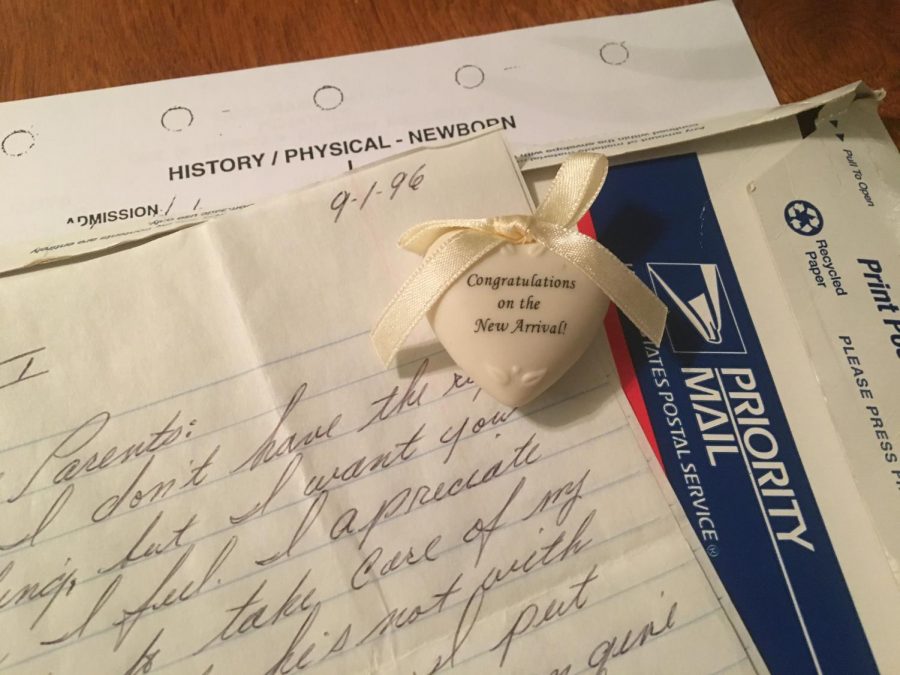

When we finally made it to El Paso I can only describe the feeling as the most familiar city I have never been to. I remember snippets of swimming in a hotel swimming pool with children asking me if I was ready to go back to school in a couple weeks (apparently schools in Texas go back in early August) and visiting the church my parents attended the day the Thomason Hospital nurses introduced me for the first time to the two people I call mom and dad. My dad and I went to the hospital .We only made it as far as the gift shop into the hospital. My dad and I crestfallen bought a small heart with the wording “Welcome on the New Arrival” and a bib that was the only thing with a hospital name on it.

The following day I met Mr. James Kirby Read. The man who arranged my adoption. A meeting I barely remember after viewing photos my dad saved of our trip. Maybe, it was because I was eight and what eight year old is prepared to bear the memory of asking an attorney what he remembered about my mother.

Forgetfulness may have been my only protection from the disappointment he could not answer my questions? That is what I told myself until I talked about that visit with my dad hours before typing these very words. As told by my dad: I talked to Mr. Read alone in a conference room because I was adamant my dad and grandpa would not come with me. My dad saying I did not believe him that I was adopted or telling the truth. What child would want to believe such a reality, even straight from their parent’s mouth?

I have not seen Mr. Read since that day, but my dad has tried to stay in touch. Once more, my dad only telling me hours earlier as I write this that he was still sending pictures of me to Mr. Read to send to my mother. My dad having to remind and confirm me to me for the third time, as he tells me, that Mr. Read tried calling my mother before we visited on the number my mother gave him years earlier.

The phone only rang and rang and rang, but no one picked up.

My mind wandering as I tried fill out the dozens of questions 23andMe makes you answer to finish you’re online testing profile. What if someone had picked up the phone? Who would have answered? What would they have said? Better states – what would my mother have said?

I can definitely tell you is I was determined. So determined in the seventh grade, I called a random Connecticut adoption lawyer I found on Google for advice. So determined I made my dad call Mr. Read and send me all the records he legally could about my adoption. Under Texas law, the report detailing the adopted child’s medical and history is edited to protect the identity of the biological parents. About a month later, I came home from school and my dad showed me a travel-battered U.S postal envelope with the records I could legally receive.

I laid on our rundown couch as my trembling hands ripped open the envelope. The several papers within the bare minimum of what I could know, but more than I have ever known in my life. Nothing that could remotely identify them, but I scavenged the bare medical records and couple paragraphs about how I was placed for adoption for details better than any NYPD officer.

My parent’s eye colors, heights, and national origin were listed. My birth weight and height recorded. However it all paled in comparison to what I learned that day. I learned her name: Mayapa. The 5’2 second child of four whose parents died when she was young. She was abused from a young age, but she went to college only to drop out two years in to work as a receptionist for a psychologist. My 5’8 father who wore glasses (yeah thanks father for giving me your eyes) only had a fifth grade education, but became a teacher. Finally listed under my mother Mayapa’s records was the words: Female – Teresa, Adopted: No, Sex: F, Age:4.

I had a sister. I had a big sister. I add 4 + 12 and realized she was at least 16. A tinge of sadness struck me at the thought I had missed her quinceañera. I had lost another chance to live the tiniest dot of my heritage. From that day, I just exhaled and said this was all I was going to learn about them. I just couldn’t continue letting my hopes raise above the surface. It was time to be in the present. A present where my racial identity was only in the early stages of forming and, to this day, is not fully solid.

One final thing, I can tell you is I grew up in a town 94 percent white and am the brown son of a white father and mother, whose maternal grandparents were racist. It’s one of the greatest paradoxes of my childhood. How could two people who watched on TV OJ’s chase on Interstate 45 shouting “Shoot him!” “Run him off the road” while my mom walked away in shame never say a word or commit an act against their Mexican-American grandson? I will never know and my dad can never explain it, but maybe they did not see me as person of color and only their grandchild.

My racial identity since the day I learned I was adopted is completely forged by myself alone. An identity ducted taped and stitched together not by family pass downs or learning by adjacency to friends who shared my heritage, but repressing the pain when a classmate told me to show my green card, when I have to indulge student jokes about being Mexican-American (The Day After Tomorrow scene of Americans crossing into Mexico still makes me cringe thinking about how a classmate in my science class joked he should be nice to me if something like that happened), and the rare acts of empathy.

I’ll never forget when after class my high school Spanish teacher, Mrs. Galvez, a white woman married to man she met studying in Peru who were raising their young biracial son, invited me and my dad to join her family to a party in her predominately Latino neighborhood. I never took the invitation seriously or told my dad, but it remains one of the kindest acts someone has ever done for me.

I chuckled to myself remembering all these events from long years passed. Memories I had to dust off because I’ve tried to bury them, but not forget them. As I sealed the 23andMe box kit so it was ready for mailing, I couldn’t decide if it was the ancestry kit, that it was my Aunt Beth’s funeral the next morning, or both that was causing all these memories to rush back.

When I had gotten this kit after attending summer taping of The View I wanted to hold off using the kit, but I didn’t plan on holding off till the night before my aunt’s funeral. The universe is such an ironic bitch. To learn about the heritage of a family you had for seven days, while laying to rest one of the people who welcomed you into their family after those seven days.

Before, I went to sleep that night I looked back at the table. The thought capturing my mind. Should I threw out the kit? Do I even want to know? What if what it says counters the identity I have? What if says nothing but I’m from Mexico. I wanted to know everything I could, I always have, but what if I regretted it?

It was those same thoughts filling my mind a little over three weeks later on Oct. 31, at 10:59 p.m. when I received an email from 23andMe. The subject headline: “Your reports are ready.” The headline so generic and gimmicky.

A more appropriate headline maybe: “Hey! You want to know or not.”

It was a question I struggled with for close to another five weeks. The time never seemed right. What was the appropriate setting and time to learn your ancestry? In the library after a class or in the evening on the train ride back from your internship? Apparently the right time is sitting with your dad with a couple plates of grill cheese for lunch the Saturday after Thanksgiving.

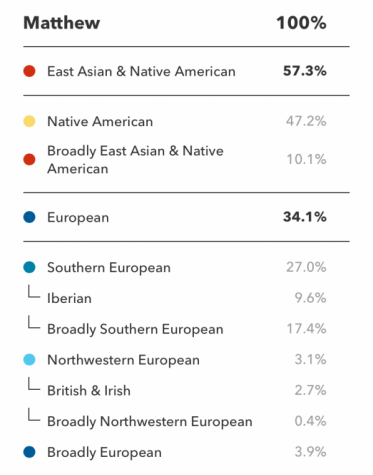

I am 47.2 percent Native American. I exhaled a large breathe I didn’t realize I was holding in. I felt a tinge of happiness and pride. I do not know what tribe(s), but I’m interpreting it to mean I’m of tribe(s) mainly in Mexico and Southwest United States. The more proper term may be “indigenous” to describe what it means. Am I still Latino or is Native American/Indigenous more appropriate? A question better suited for another day.

As I read the rest of my ancestry profile, my dad sat silently listening. I am an additional 10.1 percent under “Broadly East Asian & Native American.” An occurrence attributed because 23andMe finds DNA between those of East Asian and Native American are incredibly similar and my maternal haplogroup, the human line from which I descend on my maternal, is C1 which can be found among the Japanese, Eastern China, and Mongolia reaching Central Russia. I am also 27% percent Southern European with 9.6 percent Iberian (Spain and Portugal). Some of my ancestry is so spread across certain parts of the world across multiple generations it is difficult to know what specific regions or countries to apply it too.

As I finished reading the palate of colored words on my phone my dad picked up his plate. Him smiling at me as he says how interesting it was to hear that. His tone light, but cautious. My tone no different than his. I did not feel a transformation or sense of hype. Maybe, because since the day in the seventh grade my dad and I had an unspoken pact to not let our hopes ever rise. Too many conversations of what he remembered and what I would never remember. Too many hopes raised when I still had a bedtime.

As the grandfather clock rang three times later that night, I sat on the couch. Fifteen hours before my dad would drive me to the train station and end my Thanksgiving break. My hands trembling as I held a letter my mother wrote to the parents who would adopt me on August, 1, 1996. About 28 days before I was born. I was at the bottom of the papers I received on the seventh grade. I have only read it twice in my life before. Once, on the day I laid my eyes on it in that U.S postal envelope and a couple days later. As far as I know, my dad has only read it once that first day.

I held the letter as firmly and gentle as possible afraid the letter would burst into dust. The letter written in cursive with pen in well-spoken English. The full content of that letter will only be for me, but I believe my mother would be okay with me sharing this section. I think she would want more than only me to know this…

“…Even though he’s not with me he’s still my son. I put him in your hands so you can give him a lot of love and be there when he needs you; you know when my daughter is asleep I feel happy cause she knows there is somebody when she wake-up. Now I hope my son will feel the same way.”

I did feel the same way, even when I was most uncertain or in doubt. Thank you Mayapa, thank you mother, for everything.

I love you.

– Your Son

Matt Reich is a guy constantly on the go who can't let a minute go unused. Born in a city in Texas, raised in rural Connecticut, and now he's trying to...