Higher Education Behind Bars: Inmate Heals Through The Arts

You walk into a room with a few dozen desks, sit down next to your fellow classmates, and face the dark green chalkboard. You pull out your notebook, write your name and the date at the top of the page, and wait for your professor. You’re eager to learn and hopeful that this week’s discussion will expand your horizons.

Sounds like your everyday classroom. Well, it is, except that it’s in the middle of a maximum-security prison.

Welcome to Sing Sing Correctional Facility, and class is now in session.

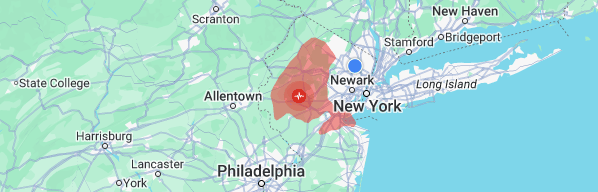

The Hudson Link program provides college education to incarcerated and formerly incarcerated men and women, in New York state, to help them make a positive impact on their own lives.

They have awarded over 500 degrees through eight colleges and six correctional facilities over the past 19 years, according to the organization. Robert Pollock earned his Associates Degree in Behavioral Science from Mercy College, and he says earning that degree has changed his life completely.

Pollock, who was incarcerated for more than eight years, asked for an educational transfer to Sing Sing specifically to obtain his degree.

“It was the first time I experienced school as communal,” mentioned Pollock. “It was very different from previous colleges I’ve gone to.”

He found joy in class discussions and the camaraderie that came with ponderings that took place outside of the classroom with fellow classmates.

At the correctional facility, higher education classes are held at night and inmates must be on good behavior to be able to participate. Members of the Hudson Link program also become eligible for parole sooner than they normally would.

Pollock described the professors as “very enthusiastic” about the inmates continuing their education. It quickly became a positive learning environment. Obtaining knowledge about psychology and social behaviors helped him gain a greater understanding of the human mind and provided him with guidance during his difficult period of incarceration.

“Learning about Behavioral Science helped provide a cognitive framework for many things that have happened in my life”

“Am I a good guy or a bad guy?” he thought to himself when he was first incarcerated.

He soon realized through discussions with his fellow classmates that many inmates feel they are the worst for where they’ve ended up in life, but through the power of higher education, the outlook changed for Pollock.

While other individuals attending college have access to endless resources, Sing Sing Correctional Facility only has a library for the inmates to use. There’s no internet and certainly no computers. This was just one of the many obstacles Pollock had to overcome.

“My mom was so supportive – she would send me pages and pages of research for my classes,” he stated.

And while many inmates ask family members to send them research, Sing Sing regulates the intake of letters so that each letter is only allowed to contain seven pages. So even with outside help, there were many restrictions.

By simply walking down the rows of cells at Sing Sing, it’s easy for one to pinpoint which inmates are working towards their degree and which aren’t. The inmate who is tucked away in a cell reading a book or studying is likely the student. The inmate who is out in the yard starting trouble, is not.

“They are some very dedicated guys,” said Pollock politely, who leaves the alternative to your imagination.

Along with expanding his world through learning about social behaviors, attending classes helped Pollock grasp the importance of other art forms.

With the help of Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA), he recently played Lt. Daniel Kaffee in a theatrical production of A Few Good Men.

RTA is another program offered in maximum-security facilities to help inmates develop social and cognitive skills to aid with adapting to life when they are released.

“There’s a huge difference between just being in a play and understanding the literary elements behind it,” Pollock expressed.

Before being incarcerated, Pollock experimented with guitar playing, but behind bars is where his passion for it blossomed.

Sing Sing offered classes to the self-described “mediocre” guitar player and he soon became involved with Carnegie Hall’s Musical Connections program, where he found freedom through musical projects through the organization.

As his musical abilities grew, so did his self-assurance. Pollock became the music room clerk at Sing Sing where he taught other inmates how to play the guitar. The friendships he created during this time of teaming up to write songs and having jam sessions have lasted even outside of prison.

“Whether it’s in music or just in life, it’s nice to know that I have these people who understand what I’ve gone through,” he mentioned.

Pollock’s sketching abilities became more refined behind bars, as well.

While on a visit to Sing Sing, his now fiancé noticed how children are affected by a parent being incarcerated. She noticed how hard it was for children to leave their fathers after a visit, not understanding why they couldn’t come home with them. It wasn’t just one child – she noticed many children who were affected by the prison system.

She came to Pollock with the idea of creating a children’s book that can be a resource for families with children who have an incarcerated parent. His fiancé would write the story and Pollock was in charge of the visuals.

From behind the steel bars of his cell, Pollock created the illustrations for “Sing, Sing, Midnight!”, a story about a little girl named Maya who represents the nearly 2 million American children with an incarcerated parent.

Self-publishing this book was a challenge, as the two were only able to communicate through letters.

“I feel so grateful that I was able to experience everything I have,” Pollock said, “even though I feel that I didn’t even deserve it.”

Since his release in Sept. 2016, Pollock has been living in New York, working as a bike messenger and continuing his self-exploration through the arts.

He graciously admits that without music, his experiences would have been more difficult to overcome. He finds himself writing and recording songs that reflect his feelings and views of the world.

“I still look at life pretty positively,” he added. “Even after everything I’ve been through.”

Olivia Meier, most commonly referred to as Liv, is a journalism student at Mercy College. And while she loves New York, she is a true Jersey girl. If she’s...